Halo

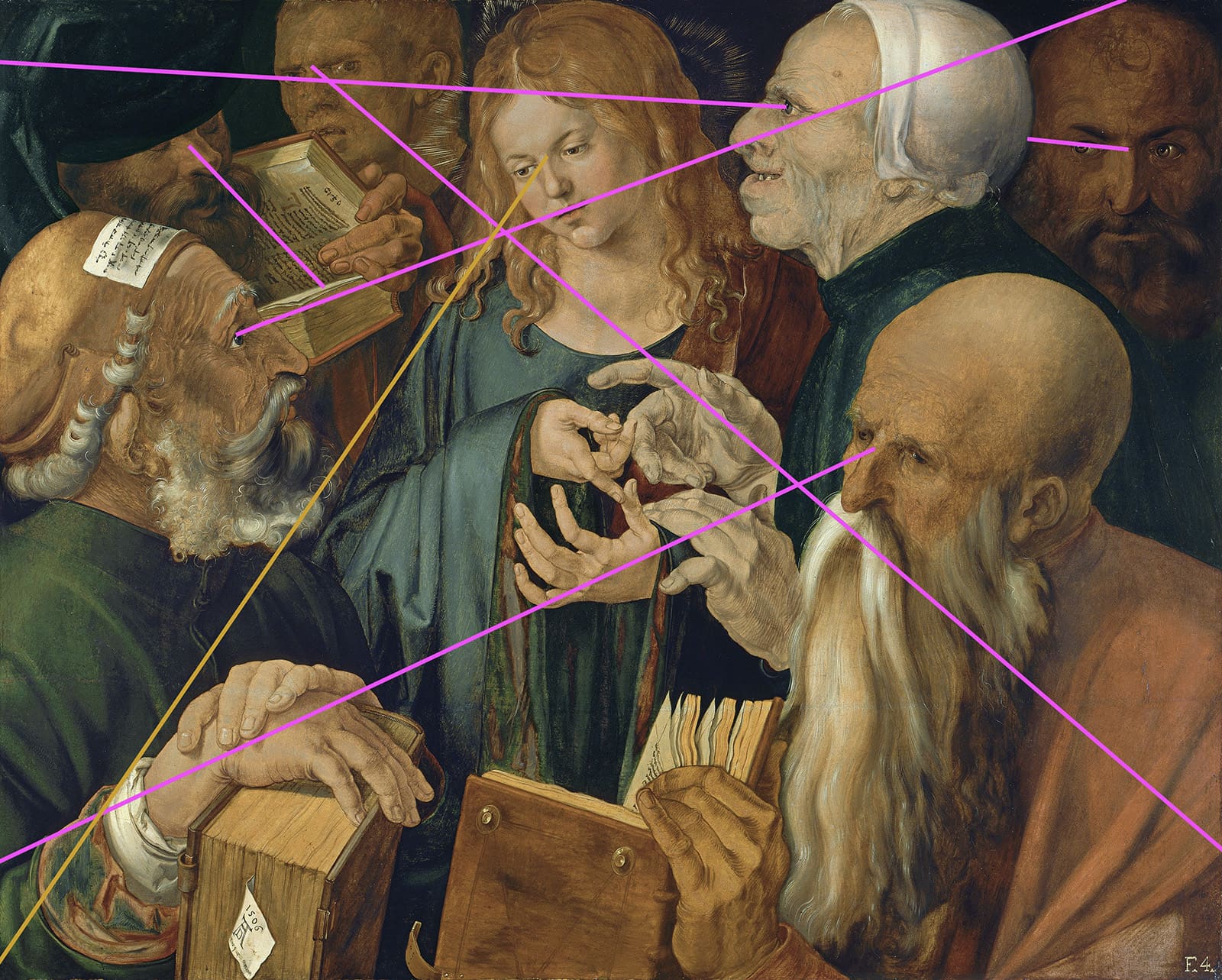

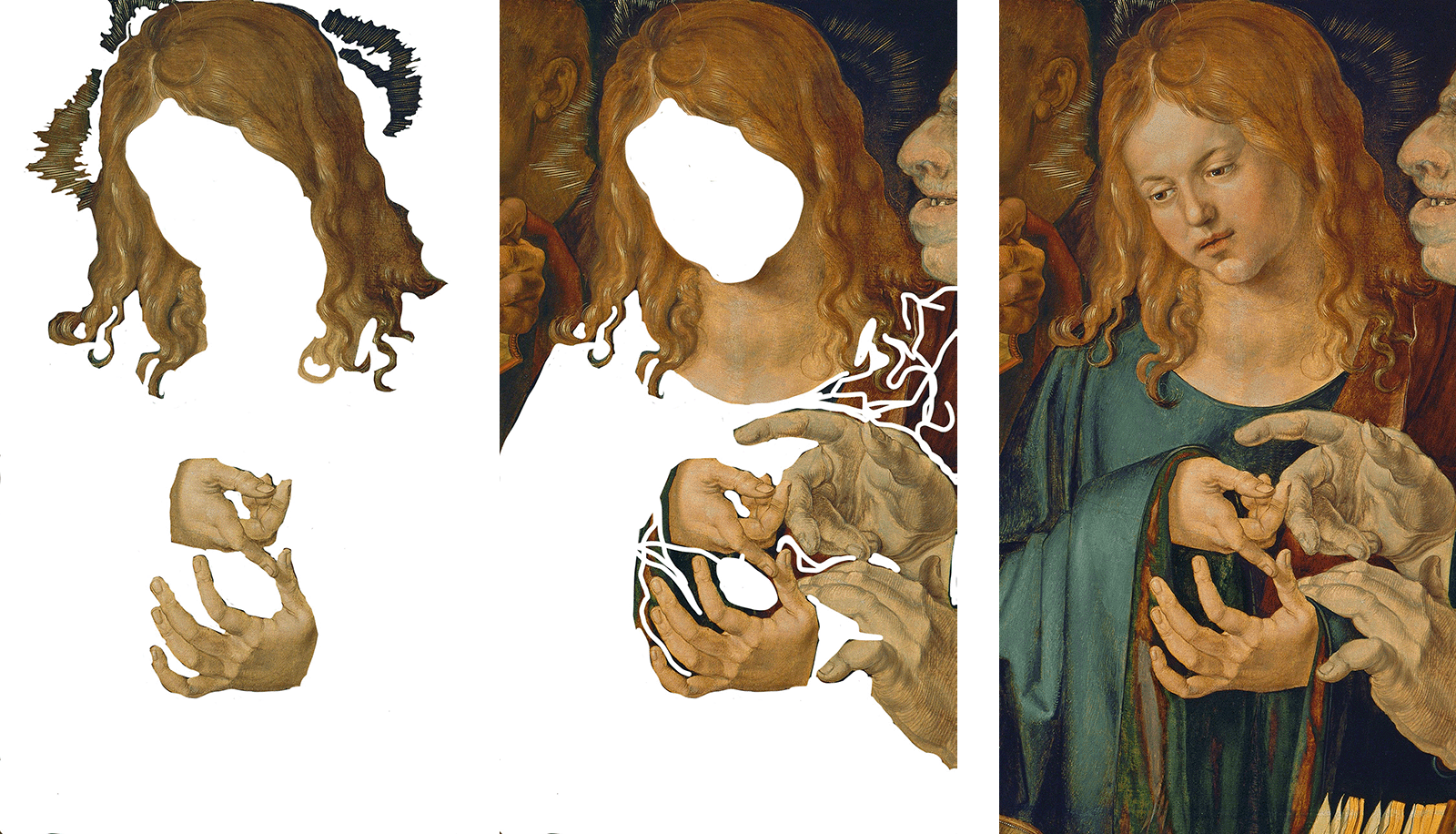

Dürer, Albrecht. Christ among the Doctors. 1506

In Albrecht Durër’s Christ among the Doctors, only one of the elders has his hands on the boy Jesus. The other pharisees jockey weighty tomes or hover ominously in the background, brandishing the whites of their eyes. The one who touches Jesus presses down on the boy’s left arm with his left hand. His pinky drops at an odd angle, and the space that opens between it and his ring finger yawns like a mouth. The void is echoed above in the elder’s right hand, this time with his fore and middle fingers: two beaks nipping at the Lord, circling his heart. The others with their books — their fingers also gather and fold, crimp and sharpen. They are spears cleaving old arguments or they are layers of mud under which a sacred text is buried. Only Jesus’ hands are empty. Only Jesus’ hands curl upward. He counts his arguments, but his fingers unfurl like a Morning Glory, perhaps to catch the gossamer light from his halo.

The painting depicts a story from the Bible, “The Finding in the Temple.” Following Passover, Mary and Joseph discover that they’ve left their son behind in Jerusalem. They return to the city and find Jesus sitting among the elders in the house of worship, asking and answering questions. He amazes all who hear him. The loss of the boy is the Third Sorrow of Mary. Finding him is the Fifth Joyful Mystery, a rosary meditation. In Catholicism, you can’t know joy without first knowing sorrow.

It’s safe to say that I don’t know god anymore (I might never have known them). I no longer attend Mass regularly, nor even sporadically. It’s been well over a decade since my last confession. When people ask, I say I’m post-Catholic, by which I mean I’ve left the dogma behind, yet the ritual and depth of my religious upbringing can’t now be separated from my sense of the world. Catholicism is the lens through which I perceive mystery. It’s also the lens through which I consider pain, so closely aligned as the faith is with trauma. Revelation through suffering was a constant lesson in Catholic school, which I attended all my life. Once, a nun, having overheard me curse on the playground, claimed that Jesus’ heart bled whenever I said a dirty word.

Back then, I made confession monthly, and though I know they’re different sacraments, reconciliation was a kind of marriage, binding together in my heart the fear of what I’d done with entombment. Consequently, I always sweated while inside the box. I always smelled my collecting odor and felt my hands shake, clammy and slick to the touch. I feared the stench I left behind for the next sorry soul. (The box would be a marvelous place to think and pray, if not for the little window and its exquisite screen, the other voice slipping through like a poison.)

Tellingly, the results were always the same, an atonement unequal to but in honor of the crucifix. Every wound, whether physical or abstract, was considered alongside the stigmata, so the suffering of my life has been washed in their blood. All of which is to say that I can still have a crisis of faith even now, even though I’ve stopped believing. There is no crisis without faith. There are no crises that do not also make me, without thinking, consider their name and suffering.

Such invocations spring from the tired impulse to summon help when I feel powerless. They are no doubt entirely selfish. Yet the dynamic reverberates. I call their name and demand a fleeting proximity; even if the catastrophe can’t be averted, it can be placed at their feet. It can be sanctified. Revelation comes through suffering, and that makes all suffering holy. This is especially true in retrospect, when I want the larger moments of my life to bear some existential logic equal in magnitude to the way I remember them, to the way they made and still make me feel. This is a long way of saying that when in pain, I look for the mystery, that when I have to make sense of chaos, I turn, reflexively, toward the faces of god.

Giotto. Last Supper. 1306

When my daughter was just shy of three years old, she fell backwards off a swing. I didn’t see her fall, but I remember her sudden screams. I remember turning and finding her splayed on the ground, writhing in the dirt. She cried in a new way, into a deeper hurt, and her face twisted strangely. I didn’t know it yet, but she was concussed, and her right hand hovered above her forehead, trembling. My daughter was scared to touch herself, which was a kind of reverence, her hand stilled in awe of the pain. In its reluctance, it suggested a territory around her head she dare not trespass, something like a sacred space. Something like a halo.

The halo is a kind of blasphemy. The word comes from Byzantine Greek, a descendent of halonion, or threshing floor, the flattened surface on which farmers separated the grain from the chaff, often through flailing or beating. The relationship is visual, as threshing floors were often smooth and circular, qualities echoed, to great variation, across Christian iconography. In some works, the halo flatly circumscribes the head, as in Giotto’s Last Supper. Other times it attempts to honor three-dimensional space; Massacio’s The Tribute Money casts each halo as a brassy plate precariously balanced.

Sometimes the halo is more ethereal, nothing more than bits of light emanating from the body. The radiance encircling the head of the young Jesus in Dürer’s Christ among the Doctors is subtle and uneven, nearly humble, a needled glow picketing reddish hair. Variations such as these, wherein the light seems to spill, wherein the flow of grace and power is outward, are the most troubling. It’s as if the soul were too much for the body encasing it. The body of Christ leaks, which it’s not supposed to do until the very end. Supposedly, what’s sacred is not the spirit rushing forth, the escaping light, but the union of the divine and the mortal. What’s sacred is the incarnation, the wholeness. The fact that nothing passes through.

This is how I sometimes consider the nature of my daughter’s concussion, as a breach that exceeds the body, as ominous spillage. Sometimes, then, the language and imagery of my religion feel appropriate. Sometimes they seem the ideal tools for translating this experience. Another example: during the Emergency Room visit that followed my daughter’s accident, the nurses couldn’t find the veins in her arm. They wanted to prep an intravenous cannula on her hand, just in case she needed, suddenly, an injection. For a while, the search was fruitless. They probed her forearm, kneading her skin and squeezing her muscles. They brought her wrist up to the tips of their noses and stared skeptically. Eventually, they decided to make shadows of her veins. They shut off the buzzing fluorescent tubes, and they held her hand reverently, as if to kneel down and kiss it. Instead, they pressed the bulb of a flashlight into the meat of her downturned palm, and the light passed through her skin as though it were a veil. Her hand glowed, and I was unsettled at how porous her substance was. My daughter ceased, momentarily, to have an edge. The borders of her palm dissolved into pink glimmer. I wanted to cup the spilling light and drink it. It passed through her muscle and skin, but her blood, it’s iron and oxygen, absorbed it. Suddenly, the many dark and throbbing corridors. How not to recall, in that moment, the image of god I was given as a child, that of a man spilling his blood and water?

This is an effort to read the story of my daughter’s fall (read as in study, read as in understand, read as in accept). This essay is the story of that failure. Why else begin with a painting, with an approximation of god? Why not start with the daughter slipping from the rubber seat of the swing?

I began with Durër’s work because of its understated halo, which lies somewhere between there and not there. I see its glimmering, and I’m reminded of the ambiguity of my daughter’s injury, how it was and became more than what transpired inside her skull (a sudden interaction with her mortality, the consuming fear of her potential loss). The analogy is both reductive and sensational. The danger is in how the space between faith and fear narrows, how religious glory then aggrandizes (blasphemes) justifiable panic. The injury, through its sanctification, becomes more than it should, and its consequent holiness is suddenly capable of permanence (sacred things must be held onto, must be fervently remembered). So instead of through, one moves only deeper into.

And if I go deeper into Durër’s work, I recognize the principal sin it dramatizes. The hands in his painting tell a story of skepticism and contention. They denote an exegetical power struggle. But the eyes of the painting reveal neglect. No one looks into the eyes of another. Or, if one traces the paths of their looking, it seems every figure gazes over a shoulder, stares across a face, or studies an object just beyond the edge of the scene. But this assumes a false parity. In the reality of Durër’s composition, it’s Jesus who stands at the center of the work, Jesus who requires attention, Jesus who is meant to be looked upon. Several transgressions are rendered, such as arrogance and doubt, but the greatest seems to be one of omission. The doctors, those fatherly figures of the church, fail to see Jesus. They fail to witness the child who glows in front of them.

I can’t read, then, the story of my daughter’s accident without also fixating on my own culpability (never mind that someone else was watching her). I didn’t see her fall; I didn’t see the making of the injury. This is the Catholic reading, wherein blame must be positioned, wherein the moral ledger must account for all participants, including bystanders (“you will disown me three times”1). An MRI taken in the middle of the night was the closest I came to “witnessing” the concussion. But only just so, because on film the injury looked nothing like perilous rupture. On film, it was a trail of radiant salt at the base of my daughter’s skull. On film, it was the pearl root of an unknown tree. The image failed to be the injury; in the end, it was the approximation of a wound.

The honest truth is that what I know of god is interpretation, and that knowledge has become an obfuscating impulse. So the desire to interpret, to cast the biological as spiritual, ultimately obscures. I don’t see my daughter’s face, only the aura around her head. This is a kind of blindness. It’s also an echo of Catholic remove, of revelation apprehended vicariously (the priest fetches the body of god on my behalf). To know vicariously is to witness from around the corner. It is a way of seeing without looking.

I’ve since cultivated a greater sympathy for Thomas who was incredulous. In the eyes of the other apostles, he doubted. In his own heart, he lacked. He was jealous of those who saw and afraid that his own faith was the lesser for it. But the touching, his contact with the wounds of Christ, brought him the dregs of the miracle, what remained to be seen. I’ve wanted the same thing, to witness whatever was left to witness. Here, I read toward a Catholic sense of empathy. How else to describe the portrait of Mary, Mother of God, in Annibale Carracci’s Pietà with Two Angels, except as ecstatic mirror? Her mouth and her son’s gape to the same darkness, to commensurate rows of childish teeth. Christ’s hair, both of his head and of his nebulous beard, blur at his neck, and the shadow spills onto his mother’s chest. And though Mary breathes, her fingernails are sapped of color, drained to gray as the fingers of Jesus. Even their heads are bound by the same wispy halo, by identical tracings. Mother and child appear to dream the same dream (or nightmare). This is one Catholic argument for the nature of love (though this love is obviously gendered and fixed to motherhood). Its conclusions are fatal.

Carracci, Annibale. Pietà with Two Angels. 1603

In the realm of devotion, Carracci’s work is the norm, not the exception. In every painting I’ve ever seen of the dead Christ, of the lamentation of his death, he lies atop a stone or a person, most often his mother. The image is cyclic, Jesus collapsing back into the form of Mary; she who brought him into the world now carries him out.

But there are no corresponding portraits of Joseph with Jesus. The absence of this imagery is logical and reasonable; by this point in the life of Christ, the earthly father is long gone.

He has since died of old age, an event not recorded or alluded to in the New Testament. In fact, the story of finding Jesus in the temple (the scene of Durër’s painting) is also the last story of Joseph, alive and present, in the gospels. Thereafter, he vanishes, which means that later on, when Jesus is nailed to the cross and crying out in pain, Joseph won’t be there to answer him. It is as though his initial absence — yes, the child was left behind, but from Jesus’ perspective, it’s the parents who are gone — magnifies and expands. It evolves quietly and unremarkably toward permanence. The loss of the child also means the death of the parents.

I don’t know if this is a poor appraisal of Durër’s work. To read this way is to move beyond the boundaries of the image, to want more than is offered. But the missing parents can be felt in the scattershot eyes, in the hands closing in on the figure of Christ. Their absence is suggested by the frame, as the negative space includes those whose duty it is to care for the innocent, to protect him. And here is the ecstatic stretch, the interpretive overreach, as I start to consider the distance between me and the swing my daughter flew from, whether one could say I was beyond the frame of her body at that moment. This also is the deeper into, where the story shifts away from what happened — my daughter fell, I took her to the hospital, I watched her through the night — and instead seeks a moral reckoning. Her survival is overwhelmed by this accounting. It’s the same mistake as viewing Durër’s work and interrogating the doctors’ eyes, forgetting that the scene dramatizes a miracle, that it shows people talking directly to god.

I know that these analogies are melodramatic. To indulge them is to allow the residue of my Catholic faith to magnify the desperate emotions surrounding my daughter’s medical event. I’ve tended to treat this kind of thinking as peripheral, as though it represents the outer edges of my consciousness, the extreme versions of my worldview. And yet, the reach and persistence of this religious verdigris sometimes proves boundless, less radical and more fundamental than I have imagined or admitted. But can’t something be sacred without gesturing toward death? Is that where all sanctity lies? When I think of those events, of my daughter’s injury, I feel as though I’ve stopped at sorrow, as though I’ve spent all my prayers on Good Friday.

It’s a crisis when the imagery and narratives of faith distort rather than clarify. I’ve tried to know something of that timethe instance of my daughter’s fall, the text of her injury — by filtering what I saw and felt through these personal relics. Yet, the lens of my ambiguous and wavering religiosity is made from the darkest glass. The temptation is what that lens demands of me, how I’ve been trained to look so closely through it, such that other perspectives feel shallow by comparison. I am guilty, then, of honoring false hierarchies, of worshipping false gods, and by that, I mean this thinking has brought me no closer to an understanding of my daughter, that danger, or the significance of that event.

This is not an essay but, rather, a selfish enterprise, a hoarding. These pages are an effort to possess, to place a minor calamity within a certain context and to contain it. It is true that every earnest Catholic has the duty to contain, to place a god in one’s mouth and swallow. I served as an altar boy during middle school and junior high, and I’ve not forgotten those obligations. I attended to the bread above all else. I remember the paten, gold and sleek, the edge seeming sharp enough to cut, the center a shallow reservoir in which the priest piled the wafers, some of them broken, some of them perfect circles, a cross stamped onto each cracker. I remember the communion plate, which I held beneath the drooping chins of congregants, ready to catch any broken bits of Eucharist. The body could be moved, even jostled, but never dropped, never lost.

But I also remember the trouble with excess and the times when the priest prepared too much. A sanctioned gluttony followed, the priest consuming the remaining hosts and downing the leftover wine. He’d dust the paten clean, sweeping holy crumbs into the chalice, and he needed two or sometimes three draws to empty it. I remember the fastidious cleaning afterwards, the priest polishing the cups as a bartender might, his elbow cocked, a purificator circling the rims. He’d glow and blush, maybe from the suddenness of all that alcohol, maybe from the effort. But it showed on the skin and in the sweat drawn by the altar lights. I felt it, too, whenever I took the blood along with the body. The wine often made me queasy. It tasted sour and alkaline, and it dried out my mouth before tumbling down into my fasting stomach. I burned under the black cassock with its tight collar, and the heat amplified my nausea. I struggled sometimes to hold myself together, which is to say my body struggled to be a sacred border.

Every metaphor is a system. Every metaphor is an intermediary. The work of the metaphor is to limit and organize. The work of the metaphor is to carry me across. Faith might be the wisdom a metaphor generates outside of itself, unwieldy and beyond possession. I don’t mean a faith in god.

These memories, side by side, are a metaphor: The first time I took my daughter to Christmas Mass, the church overflowed. Wayward Catholics, I among them, spilled out of the pews and lined the walls. Three months old, my daughter could barely see. But she could feel the heat coming from my body, the air sweaty from the outsize holiday crowd, and for most of the service, she slept in my arms. Yet, when I sang, her eyes slowly blinked, as if looking for the words. At that age, she often wanted to touch my face. I’d sometimes put a finger on her lips, gently, in response. I’d say mouth, ridiculous in my hope that this would teach her something. I’m well beyond the miracle of her speaking, though I can remember the wonder, in that first year, of imagining her voice. At the time, I only wanted one word from her, for her to call my name. In the communion line, I sang the hymn and pressed her to my chest. I stopped only to tell the priest, I am not worthy, but only say the word…Then, years later, in the September after her accident, I took her to a neurologist for a follow-up. She’d arrived at that moment without further incident, without another fall or injury. The doctor looked into her eyes, and he asked her to punch his hand with her little fists. He checked all her reflexes, tapping every joint. The last thing he did was ask her to run down the hallway. He wanted to watch her body in motion, to see if there was a hitch in her gait or a strange jerk in her swinging arms. But my daughter was scared, and she clung to my leg. She wouldn’t leave my side. The doctor implored, and she refused. Eventually, I pried her hands off my body, and because I wanted so badly to know that she was fine, that nothing lingered from her fall, I ran away from her. Her eyes grew large, and she chased after me, yelling daddy, daddy, daddy, daddy!

It’s important that I admit my own ignorance (another Catholic lesson): I have no idea how long it takes for a calling to get its response. And sometimes it does seem possible to read my life as mildly epiphanic; there are moments when I can suddenly apprehend, though I still fail to say exactly what it is I grasp. This is a metaphor for humility. These pages also fail, though it’s the failure that translates into knowledge: these pages can’t contain my daughter or what happened to her. They can’t contain or relate the sanctity of whatever it is I saw or see in her injury. In both cases, there’s simply too much. I wish I could speak directly to those things, but I also wish I could speak directly to the almighty. A confession: the deficit is mine. I’m too accustomed to the limits of the old religion. I have nothing to say about the blood that spilled inside my daughter’s head. If I’ve been called, I’ve been called to witness, which is not the same as being called to testify. I’m stuck on the halo, with its intoxicating suggestions, with its escaping light.

-

Matthew 26:34. New International Version. ↩︎