You Can Never Go Home Again

In Alexandra Chang’s short story, “Farewell, Hank,” a woman named Adrienne fumes over her neighbor’s collection of Orientalist kitsch: a print of a watercolored pagoda, zodiac figurines, a shower curtain depicting orchids and bamboo shoots. It doesn’t matter that her neighbor is from China, for Adrienne — herself the daughter of Chinese immigrants — the lurid display nauseates her, “[bears] down on Adrienne with all of its tacky ancestral weight.” These baubles, as for many Asian Americans, evoke an overplayed exoticism, a reduction of heritage to caricature. The narrator states, “It was reaching for some other time, some other place, had gotten some of the signifiers but had missed, and thus achieved something else entirely.” Adrienne finds herself culturally estranged, lost in a home that is not her own.

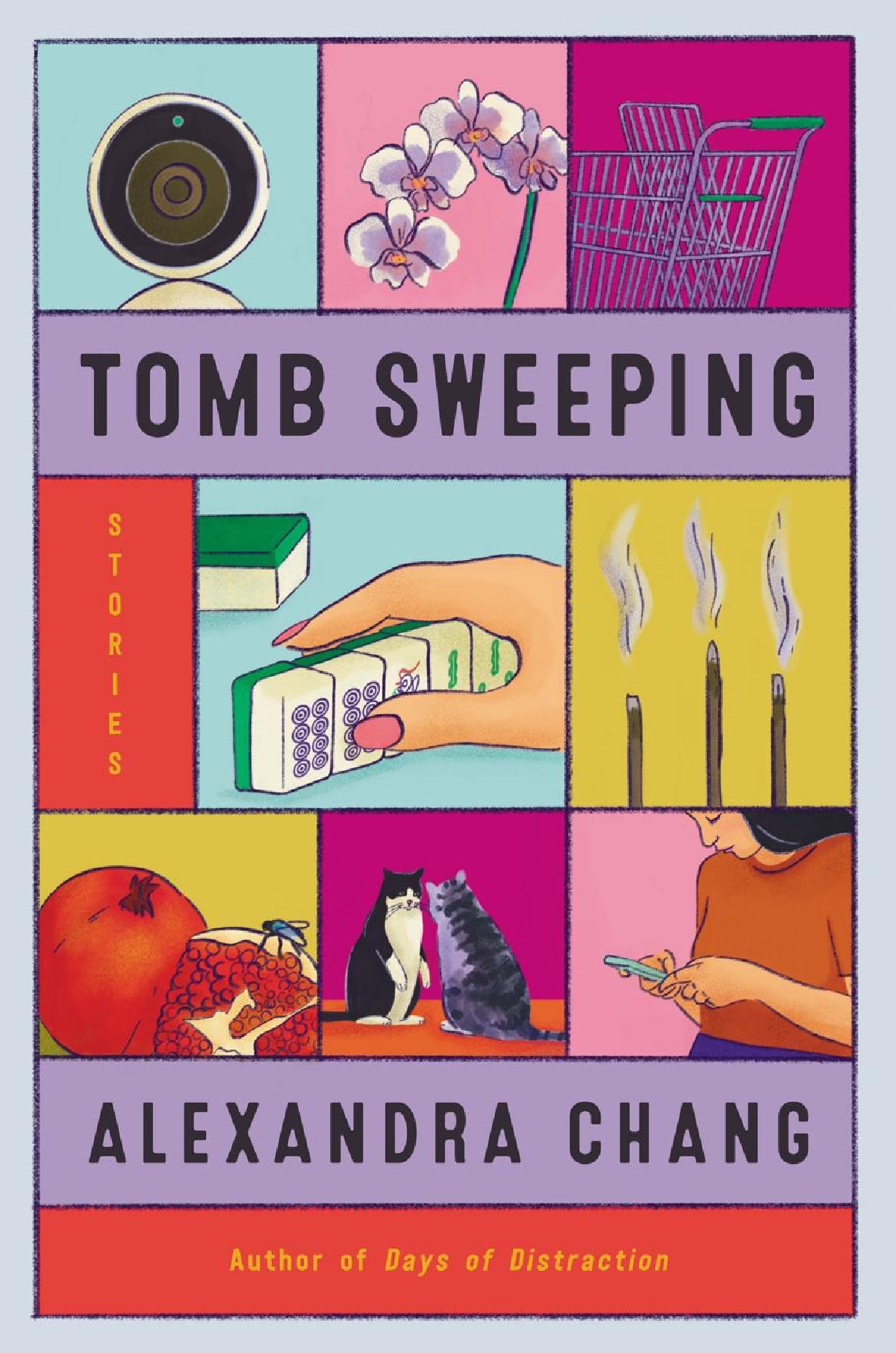

Estrangement is a recurrent theme in Alexandra Chang’s new short story collection, Tomb Sweeping, refracted through characters alienated from parents and partners, from their homeland and even from their own selves. As Chang’s stories span the Chinese American diaspora, she braids this theme with issues of cultural hybridity and purpose, opportunity and generational grief. An immigrant finds herself living on the streets after the sudden death of her husband. A young woman reflects after meeting a man who is obsessed with her doppelganger. But as Chang contributes to something that resembles narrative plenitude (borrowing a term from author Viet Thanh Nguyen) for the Chinese American experience, her collection invites a reckoning of Asian American literature today: What becomes of a genre that once found its coda in American acceptance? How does this literature proceed with the disaffection of subsequent generations? Denied a way forward and a way back, many hybrid Americans find themselves estranged from a spiritual home.

Chang’s stories read like vignettes, expositions in a first or third-person point of view. “He does not yet know it,” the narrator in “She Will Be a Swimmer” begins, “But this is the year when his life ends…He will come to perceive this when he is much older, looking back.” Individual lives, as in “To Be Rich Is Glorious” and “Other People” are regarded in retrospection, tracing the long shadow of regret and grief. A unique example is the story “Li Fan,” the shortest of the collection, a tale of a woman whose reversal of fortune leaves her bereft in an American town called Pleasant. By recounting backward from its tragic end, the story evokes Fae Myenne Ng’s 1993 novel, Bone, which retraces the story of an American immigrant family after and before a central family tragedy. As with Ng, Chang’s inverted telling subverts stereotypes, which erase the humanity of those who fail in attaining the American Dream. By flattening her story in the present-tense, Chang lays out a life in vivisection, from its beginning with the residents of Pleasant aloof to the death of the “Asian recycling lady” (“Too new to have known her when she lived on the block”) to its conclusion, lingering with the woman’s resolute introduction: “I’m Li Fan.”

But the Author’s meditation on estrangement extends beyond nationality and race. A former tech reporter, Chang bears witness to the reach of consumerism in the modern consciousness. In “Me and My Algo,” an algorithm cruelly spells out the meaningless output of a user’s life, while in “Other People,” a woman existentially awakens after turning her remote cameras upon herself. In “Unknown by Unknown,” an unemployed house sitter — whose first-person voice echoes Chang’s narrator in her novel, Days of Distraction — reflects upon how the other half lives in the hills of Northern California. Lazing in the ample space, she made “cappuccinos with the mini La Marzocco espresso machine…rode the Peloton in the downstairs workout room…[and] would occasionally sit on a pillow in the meditation room.” Far from her budget confines, the narrator basked in “a lovely tiered garden with lavender and succulents and bamboo, along with wildflowers I couldn’t name.” In her enumeration of things, even of flora and fauna in a curated space, Chang strips her environments clean to their commodified parts. By laying bare the human need to convey meaning upon places, technology, and possessions, Chang reveals our propensity to project myths if only to hide the loneliness and the estrangement we all share. The algorithm “has nothing to do with shaping who I am,” the user in “Me and My Algo,” says. “It only reflects back to me what I want, then shows me the way.”

Nevertheless, Alexandra Chang’s stories reveal humanity through the mundane. As the title of the collection suggests, Tomb Sweeping is a nod to forbears, a meditation of our estranged ancestors, faults and all, who have stumbled before us. Humans are more than the data they create — ChatGPT be damned — and we would do well to lean into our contradictions and our messy narratives, the unbelonging that makes us feel we are a part of a greater whole. For citizens of the in-between, the endeavor may be lonely, but it can be inspiring in its possibilities. “Perhaps it’s better to think that people like me are not mixed up,” muses a spiritual medium in Chang’s titular piece, “but that we have access to more than one side of the story.”

Alexandra Chang’s short story collection Tomb Sweeping will be available August 8, 2023 from Ecco Press.