Two Halves Meld into Beige

In a way that’s intended for a larger audience, this collection sheds light onto this growing population. In particular, who do these authors represent? And what truth does this hold for readers in America?

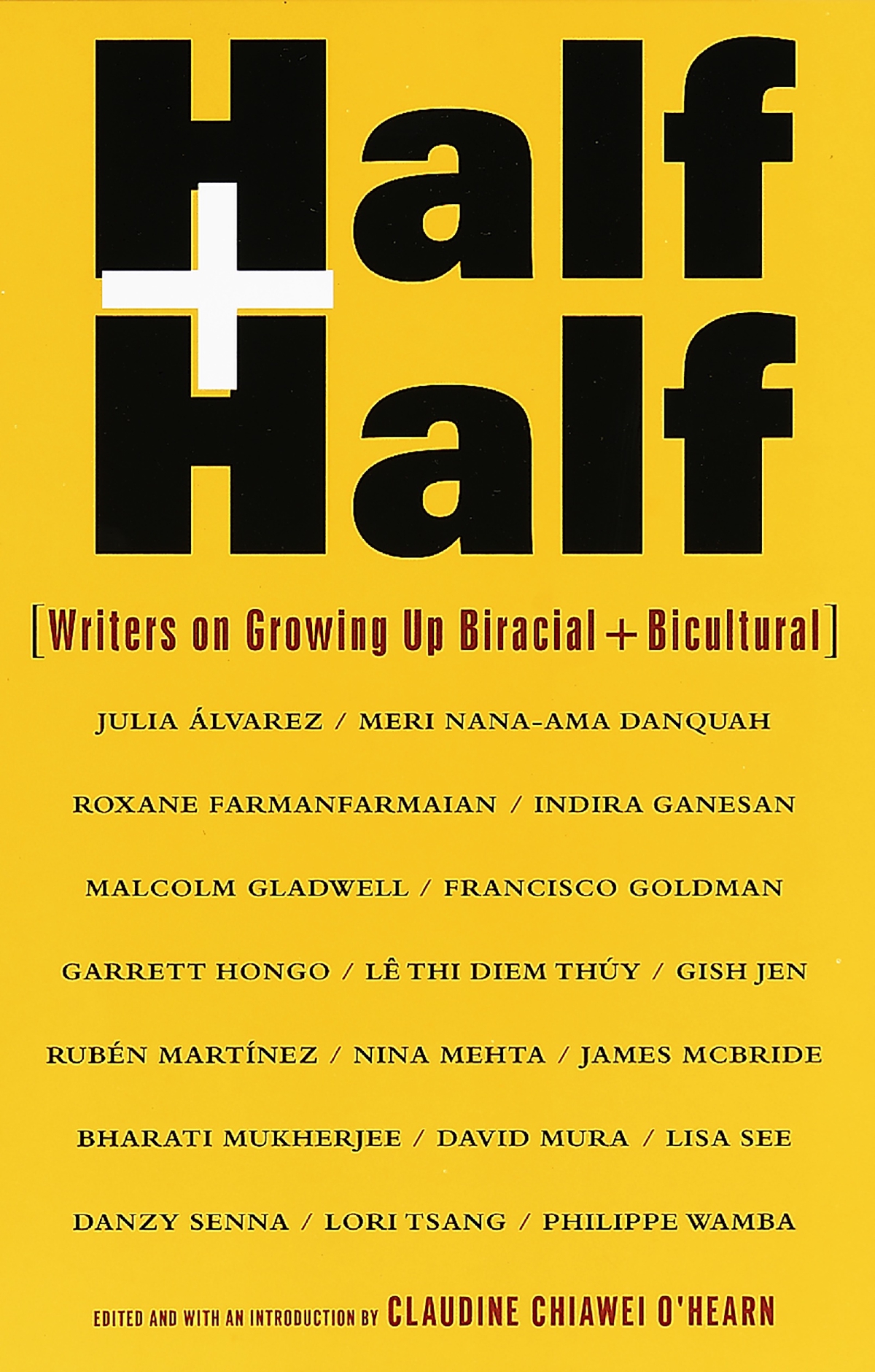

Unveiled, distinctly hybrid, and looked upon with fascination: the color brown amorphously represents Black, Asian, Latino, Middle Eastern, Native American, and Pacific Islander heritage in the United States. American authors reflect these backgrounds in the 1990s, despite the Immigration Law of 1990 that stunted non-White immigrant growth and residue of miscegenation laws. Half and Half, an essay collection published in 1998, gathered 18 biracial and bicultural voices shaped by interracial relationships and societal attitudes.

The authors from this collection are recipients and finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, the Pura Belpré award, Guggenheim fellowships, among others. They expand beyond their race and ethnicity; however, they’ve acknowledged this facet as having imprinted their lives.1

Multiracial people are defined as those who identify as multiracial, with two or more races and/or have biological parents of distinct races. Multicultural people are those who identify with more than one culture. Research on these populations blossomed in the 90s, such as Phinney’s Identity Status Model (1989), Berry’s Acculturation Model (1990), Poston’s multiracial Model (1990), and Root’ multiracial Model (1990). Dr. Analía Albuja, a psychology professor at Northeastern University, expands this work, forging a bridge between the bicultural and biracial identities in Half and Half, both with access to multiple sets of social norms. Narrative construction is a form of ‘meaning making,’ a psychological process for shaping one’s identity. Dr. Albuja, with other researchers who’ve passed the baton forward, explores development and well-being across these populations, in parallel with narratives reified of those who resisted, resigned, or flourished in the face of contradiction.

In Half and Half, Meri Nana-Ama Danquah and Philippe Wamba—bicultural authors—and Malcolm Gladwell and James McBride—biracial authors—paint the narrative of a fragmented self. Danquah described her identity as “Scattered, so fragmented, so far removed from a center. I am all and I am nothing.” Wamba echoed this sentiment: “In the end I am both African and African American—and therefore neither.” Emptiness is taking on the shape of one’s surroundings, a disconnection between distant realities. McBride vacillated between these two realities: “I’ve been running all my life.” Gladwell described this phenotypic alienation as the “nuances of color and skin and lip and curl that put me just outside the world of people.”

Such narratives undercurrent the macrosystem. Dr. Albuja grew up in rural Missouri. A small town with little immigration, where she wasn’t viewed by others as threatening but underrepresented. She sang her talent show performances in Spanish, which evoked a meaningful connection for her and a source of fascination by others. In the periphery, McBride’s “Marginal man” foregrounds the Black-White divide, documented by sociologists and felt by the individual.2

From this fragmented self, the chameleon evolves—a person who navigates different combinations of selves. Danquah says, “I am ever-changing, able to blend without detection into the colors and textures of my surroundings, a skill developed out of a need to belong, a longing to be claimed,” and Wamba says, “But even though a real chameleon may look like the green foliage it imitates, it never really becomes a leaf, and I could never fully transform myself into what I imagined a ‘real’ African American to be.” These essays are in conversation, wavering between the questions of where does a chameleon feel safe (Wamba), and how does a chameleon survive (Danquah)? Garrett Hongo, in his essay, echoes this sense of fragmentation when he reminisces to his days befriending people from distant backgrounds in California: “Yet I was aware I was crossing borders, that I couldn’t carry with me too many signs as I traveled from one neighborhood or group of folks to another.” Crossing that realm of difference can be a challenge, and it can also be an opportunity. In Indira Ganesan’s essay, she acknowledged religious customs as a tacit agreement to earn passage to both cultural doors. She understood the rules of not eating in the kitchen during menstruation with relatives in India compared to in her own home. Although it can be misperceived as inauthenticity, for a bicultural it’s resilience.

Oppression evokes empathy, at times unified by the ambiguity of brownness. Francisco Goldman, who identifies as Guatemalan-Jewish, described in his essay the tethering to race in the US to be newly misclassified as Moorish in Madrid. Denied entry into taxis and bars, he stood in solidarity with North Africans: “I remember feeling—by which I mean taking it personally—in Madrid how much this was all about denying a person’s humanity, his very existence of humiliating and even castrating him every day.” Colorism breathes through generations amid unspoken hierarchies, where every country has their own rungs. After having spoken with Dr. Albuja, she described the political dynamics in self-identifying along the axes of race and ethnicity. She was born in Ecuador. Her father is Ecuadorian, and her mother is Argentinian—two distinct cultural backgrounds. Historically, Europeans emigrated to Argentina, and 97% of the population identifies as White.3 With Latin America consolidated as one ethnic category in the US, these dynamics are often mistranslated from other countries. She described this so eloquently, the constant consideration of, Am I multiethnic? Am I multicultural? Straddling between multiple identities has motivated her work, and Julia Alvarez’s essay reflects on what it means to be Latina in the US:

“Many of us have shed customs and prejudices that oppressed our gender, race, or class on our native island and in our native countries. We should not replace these with modes of thinking that are divisive and oppressive of our rich diversity. Maybe as a group that embraces many races and differences, we Latinos can provide a positive multicultural and multiracial model to a divided America.”

Where do these collective voices reside in society? Irie in White Teeth and Niki in A Pale View of Hills introduce biracial characters as a multicultural product of the diversity in England. While I seize any opportunity to recommend Smith and Ishiguro, there’s an anchoring that this collection lacks, to which the former embeds their multiple identity characters into the Western literature rather than spotlights them at the outskirts. The authors of this collection might respond with “I’m here to detail my experience, asshole,” and fair enough. It’s compellingly done. Yet a sense of societal purpose is lost on the reader when such an existence is the alternative. That’s not to say it’s diluted. A clear divergence presents itself in the collection: the bicultural feeling two physical places at once4—in their heritage and host country—and the multiracial enduring racial politization.5 It presents the risk of this only reaching the hands of those who find it relevant (members of these identities) rather than the larger audience it may be intended for.

Overall, the line between social boundaries clarifies what the bodies of each side consist of. Once that’s defined and socially enforced, it’s the individual’s decision, with labile territorial access, to land somewhere. Multiracial identity research has more recently explored the opportunities, and more narratives have shifted to expansive belonging. Take Roxane Farmanfarmaian’s essay. Her father is Iranian Muslim, and her mother is Utahn Mormon, and that bridge is Roxane’s to forge, a mental connection between seemingly distant parts of her. She creatively binds the two in her prose—the geographic symbol of mountains, where staring at the mountains in Salt Lake City, she returns to the “dusty plain of Tehran” described by her as a double helix, where their symmetry, “seems to turn [her] mother’s country into [her] father’s, and back again.”

Through connection and isolation, the authors navigate two or more identities in a way that clutches a person that they manage to call their self. Half and Half presents experiences, which psychology examines as having consequences on well-being, such consequences complicatedly determined by diverse backgrounds. Twenty-four years later, literature by multiracial authors is farther-reaching (Mixed, a short story collection, Zauner’s Crying in H Mart, a poignant memoir, and Chee’s Edinburgh, a haunting, dreamlike novel). And literature by bicultural individuals (Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies, Diaz’s The Brief Life of Oscar Wao, and a childhood favorite, Cisneros’ La Casa en Mango Street) decorate the shelves of every bookstore. In the end, all 18 essays, who that self reflects is uniquely theirs alone to shape, and to carry.

Half and Half is available now from Pantheon Books.

-

Julia Alvarez’s In the Time of the Butterflies takes place in the Dominican Republic; Francisco Goldman draws from his own life in Monkey Boy. ↩︎

-

Seminal work by Dr. Frank Bean and Dr. Jennifer Lee worth skimming through. ↩︎

-

A paper looking at the genetic admixture in Argentina: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00556.x ↩︎

-

Le Thi Diem Thúy’s mother, who did everything in her power to preserve their Vietnamese identity, reminded her that the country would never leave her, even in America. Mura described this process: “When you grow up in two cultures … there are two distinct beings inside of you. If you’re separated from one of the cultures, that being dies, at least for a time. It has no light to bathe in, no air, no soil. It can, like certain miraculous plants and seeds, come back to life, but the longer it dwells in that state of nonbeing, the harder it is to revive.” ↩︎

-

Danzy Senna, whose biological parents are Black and White, identifies as Black: “You told us all along that we had to call ourselves black because of this so-called one drop. Now that we don’t have to anymore, we choose to. Because black is beautiful. Because black is not a burden, but a privilege.” The end of blackness is a concern of hers. It’s a complex concern that can be informed by the societal anti-black attitudes historically embedded in the US, and often thrown under the rug. While Senna is uninspired by the multiracial movement, and arguably disdainful, it’s less so a matter of exclusion to multiracial people but solidarity to a population that has demonstrated resilience. She chooses to conserve Blackness in all of its excellence, untainted. For Goldman, resistance looks like transcendence. “I can’t really blame anyone for taking the opportunity to wriggle completely free of it.” McBride’s mother taught him above all else, above all the labels imposed on him, that he’s a person. ↩︎