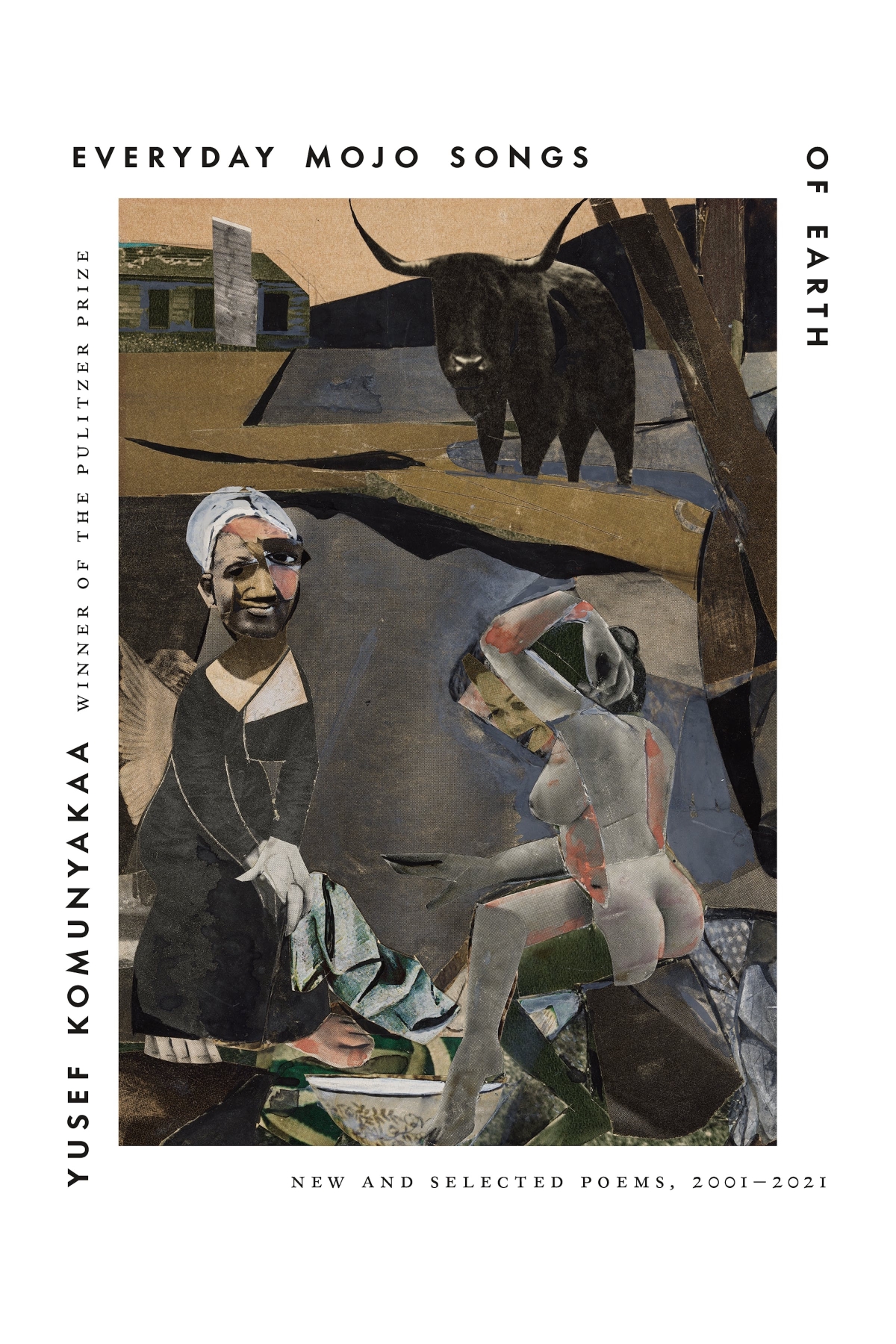

Everyday Mojo Songs of Earth: New and Selected Poems, 2001–2021

The most important aspect of Yusef Komunyakaa’s poems is that the emotive experience of the poem is not solely linked to image or lyric. Inherently, the page presents hierarchy due to the English language and its etymology as a coded system of colonial trappings. Komunyakaa’s poems expand away from the innate limitations of language. This is best exemplified by his recent work Everyday Mojo Songs of Earth, New and Selected Poems 2001–2021. In an interview with NPR, Komunyakaa described “the poet” as a “caretaker of observation.” If a poet’s call is to observe, she is an artistic curator who depends on the human senses: sight, smell, hearing, taste, touch, and the 6th– cacophonic sense. In the same interview, he described the influence of music as a “scar there in time and space” and that he does not listen to music while writing because he doesn’t want the music to “influence the rhythm of [his] own words.” He prefers words that come from a “deep place in the psyche.” If we are to observe what is outside to seek what is inward or poetic, we are contending with a concrete world of dynamic matter. From that, language attempts to characterize through a limited sensual wheel. However, Komunyakaa is a caretaker of observation, one who transmediates the multi-sensorial experience. Subsequently, we see in Everyday Mojo Songs of Earth kinetics that invite our engagement with the natural world, history, music, visual art, and philosophy.

Patience always rewards when reading Komunyakaa’s poems. Although, some of his poems immediately surprise and expand with content. For example, in the new poem “The Candlelight Lounge” compact cinquains take the reader on a journey of time travel. In the first stanza, there is a compression of three movements that transpose location and sound. Komunyakaa is known for bringing in strong references, and this poem is a metaphor for the migration of millions of African Americans escaping the oppression of Jim Crow.

All the little doors unlock in the brain as the saxophone nudges the organ & trap drums

(The reader is then taken from drums to echo, but the echo is of the 1920s)

till an echo of the Great Migration

(then, back to music)

tiptoes up & down the bass line.

This first stanza dazzles by capturing an “unlocking” of the brain through a saxophone’s nudging. Then Komunyakaa interjects a central allusion, the Great Migration. In the reverie of the bending notes of the sax, we are not jolted by the change in scene from the Candlelight Lounge because the Great Migration is presented as an echo of the past which is also a drum echo in the present.

Komunyakaa creates an unexpected turn in the third stanza:

…With one eye on the players at the Candlelight & the other on televised Olympians home is a Saturday afternoon around a kidney-shaped bar. These songs run along dirt roads & highways, crisscross lonely seas

The poem challenges by oscillating temporally and the reader discovers what Komunyakaa wants her to know: The Great Migration was a relocation of African Americans and it coincided with the growing legacy of jazz music in the United States. The tension is maintained as we move into the narrator’s space who observes the Beijing swimmer execute “a backflip, / a triple spin, a half twist, / … & jackknifes through the water, / & it is what pours out of the horn.”

In Komunyakaa’s poem “Turner’s Great Tussle with Water” he apostrophizes the viewer of the painting The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire as well as the reader of the poem. He begins with a description of skill, “As you can see, he first mastered light / & shadow, faces moving between grass…” a few lines later, a shift:

but one day while walking in windy rain on the Thames he felt he was descending a hemp ladder into the galley of a ship, down in the swollen belly of the beast with a curse, hook, & a bailing bucket, into whimper & howl, into piss & shit. He saw winds hurl sail & mast pole as the crewmen wrestled slaves dead

The “he” is the English painter of the 18th century, Joseph Mallord William Turner. In the poem, Komunyakaa confronts white gaze by rewriting the painting: “crewmen wrestled slaves dead / & half dead into a darkened whirlpool.” This act of restating and reorienting functions as a criticism of the romanticized destruction of the Carthaginian Empire by the Romans. More so, the poem deprecates the artist-as-bystander…“then the water / was stabbed & brushed til voluminous, / & the bloody sharks were on their way.”

Komunyakaa’s bold and cutting style can change to a bewildering state of empathy. In the poem “Cape Coast Castle” he narrates an irreconcilable memory of his visit to Ghana: “I could see the path / slaves traveled, & I knew when they first saw it / all their high gods knelt on the ground. / Why did I taste salt water in my mouth?” What the architecture represents consumes his imagination. Komunyakaa’s recounting of his experience exudes a sense of terror. Visuality is no less spectacular than audiality in his work. While the sound of the saxophone can be a “scar in time and space,” visual art is a medium through which Komunyakaa redirects the gaze of the viewer, the artist, as well as the reader. What Yusef Komunyakaa has achieved with the syncope in Everyday Mojo Songs of Earth is a remarkable elucidation of history through sensorial interpretation. As empathetic and committed readers of poetry, it would follow that we may also ask questions that begin with “why.”

Everyday Mojo Songs of Earth is available from Macmillan.