The Well

In Gore Verbinski’s 2002 supernatural horror film, The Ring, an adaptation of the Koji Suzuki novel by the same name, Naomi Watts stars as Rachel, a journalist investigating the disfiguration and death of her niece, who is allegedly killed after watching a cursed videotape. Rachel watches this tape, which features distressed black and white footage of what appears to be a well in a forest clearing. It is winter, the trees bare, branches reaching up into the mist. The head appears first, followed by the dirty white gown, then the bare feet: a young girl, not more than ten, crawls out of the well toward the camera, wet, waist-length hair hiding her face. Her movements are slow, lurching, horrific. Her flesh is rotten. She’s a monster.

This girl begins to haunt Rachel, the latter of whom, after further investigation, learns the former’s identity. Her name was Samara, and because of her ability to psychically burn mental images onto surfaces — and into minds — she was sent to a psychiatric ward, and later, pushed into a well by her adoptive mother, Anna. Trapped underground, Samara burns one last image of herself into the videotape in the VCR above the well in which she eventually suffocates to death. This is the cursed tape that disfigured and killed Rachel’s niece — and will do the same to all who view it, unless, like Rachel, they make a copy.

Samara haunted me, too, for years after watching The Ring. I saw something in her that I didn’t want to see in myself. Anger. Specifically, anger at being trapped — suffocated–in a young, working-class female body in a conservative suburb. I’d find her at the back of my closet. In the bathroom mirror, standing at my shoulder.

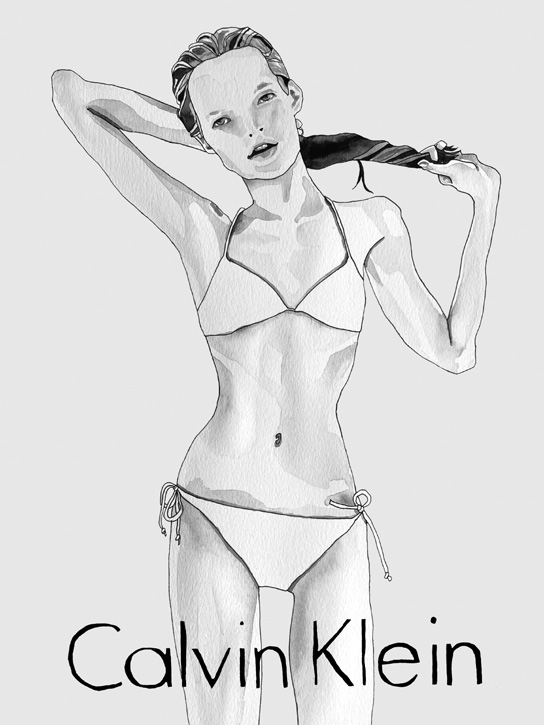

The walls of my teenage bedroom were plastered with images of models, pages torn from magazines: Lonneke Engel sitting in a shopping cart full of bowling balls for Guess, her long, dark, messy curls hanging to her waist; Guinevere Van Seenus, the eerie little blonde with heavy-lidded eyes, hunched in a shiny white trench for Jil Sander; Amber Valetta, with that high forehead doing a high kick in high heels for Versace. And then there was that backlit image of Kate Moss in a white Calvin Klein string bikini.

Kate stands contrapposto, head cocked, one hand gathering her hair at the nape of her neck, the other wringing out the wet ends, bright light shining from between her narrow thighs. The image is overexposed, her nose just two dark holes, her mouth a black oval punctuated by big front teeth. Her wide-set eyes are flat, vacant, alien, and her pointy elbows, visible ribs, and slim hips dissolve into the light behind her.

I was going to be a model, too. I thought that would get me all those luxuries models advertised. At seventeen, despite the fact that I’d be attending Columbia University that coming fall, I saw modeling as my only ticket out of town. I was only 5′9″, short for a model, but Kate Moss was only 5′7″. The casting agents at Elite Modeling Management said they’d represent me if I lost ten pounds. I approached this weight loss methodically: one Dannon light fat free yogurt for breakfast, several leaves of lettuce and three fat free turkey slices for lunch, one fat free turkey patty for dinner, plus Trident sugar-free gum all day long. I bought myself a stationary bike with summer job savings and parked it in front of the TV, riding along to whatever was on. I kept track of my daily weight in a small notebook. I lost twenty pounds, just to be safe. Then I lost ten more, just to be safer. At first, this weight loss was uniformly praised by friends and family. No matter that I had retreated from these same friends and family members — anything other than my summer job and pedaling that stationary bike. I was finally thin enough to slip through the narrow door of Kate Moss’ backlit silhouette into the glamorous life for which I’d been designed.

When I returned to Elite Modeling Management, not long after that initial visit, they rejected me. They told me I’d lost my light. A cousin told my mother I’d lost too much weight. The lab technician told me I’d lost bone density. And my psychiatrist told me I’d lost my mind. I’d lost my period, too. If I didn’t put the weight back on myself, the in-patient treatment facility would put it on for me.

Gaining the weight back was harder and took longer than losing it had. I’d dutifully swallow peanut butter by the spoonful, only to purge it back up again. I was swallowing my pride, too. While I was picked up by another agency, I wasn’t a good model. I cried at photo shoots. I dyed my hair jet black without my agent’s permission. I was stiff; photographers gave me weed to loosen me up. It was that marijuana more than the Prozac, though, that helped me keep the food down, and within a year, now a sophomore at Columbia, I’d returned to my normal weight. But that weight didn’t hang on me normally. It was all fat. I’d become flabby. My period returned; my skin broke out: a second puberty at nineteen. I looked nothing like a model. It was excruciating. I had, for a time, overlaid Kate’s image with mine in a perfect eclipse. And like an eclipse, it seared my vision, superimposing an impossible outline over my mirror reflection.

In literature, a well often symbolizes a passage from mother earth. Anna attempted to return what was monstrous to that subterranean, unconscious world. I had always been frightened by children, or perhaps I’d found childhood frightening. It wasn’t until I turned thirty-two that I was seized by the desire to have a child. I became pregnant five years later.

I was blessed with a perfectly healthy pregnancy and cursed with unhealthy thoughts about how it disfigured me. “Pregnancy can’t be easy for a woman with body image issues,” one friend observed, but what woman didn’t struggle with these? Wasn’t it only a matter of degree? I had always been good at compartmentalizing my feelings, and now I applied this skill to my flesh, avoiding the monstrous bulge in the mirror. Choosing body unconscious maternity wear: every day the same tented sweater. I refused to modify my workout regimen until one yoga instructor, in reminding me to avoid boat pose, referred to my uterine contents as parasitic. After that I shunned the studio, instead jogging three miles a day until I slipped on the ice at six months and was scared into slowing to a walk for the final trimester.

No one told me that after the baby was born, the belly remained. There it was, a droopy lump, not to mention that for weeks I walked with a hunch. My breasts had ballooned to double their size, like beached whales against my chest, and they were painful, chafed; breastfeeding didn’t come easily to me. But it did burn calories, and the weight fell from me quickly. Within three months I’d lost all twenty-six pounds. Then I lost ten more, just to be safe, running laps around McCarren Park with the jogging stroller. Other mothers wanted to fit into their old jeans, but I’d gone down a size, and it was a pleasure to feel light and girlish in a body that had just carried and nursed a child. I had abhorred the forced awareness of my body as animal — it bled and secreted — and functional: it gave life and would die. It was easier to imagine myself as decorative, and at thirty-seven I knew there wasn’t much time left for that. I thrilled in my slimmed-down image, the idea that it might soon again mirror the outline that had been burned into my mind all those years before.

But I stopped myself this time, or I should say the people who loved me stopped me: my mother, my husband, a longtime friend. Your collarbones look a bit pronounced. But you love dessert. You’re jogging in twenty-three degrees? They knew what to look out for, what to say, when to say it. While I’d never lost so much weight so as to become clinically anorexic again, over the twenty previous years I’d repeatedly approached and retreated from anorexia’s edge. They reminded me of this. They reminded me that I now had a child. It was for that child, this time with help from Lexapro, that I again returned to relative health.

It’s perfectly clear to me that those periods in which I weighed the least were also the least happy: low blood sugar-driven descents into depression. And yet that doesn’t stop me, especially during difficult times, from dreaming of that backlit image as a narrow opening into another life — until I remember that, for me, it’s a doorway to death.

In part, I wrote and drew my illustrated novel Justine in an attempt to exorcise the demon. The very first page of the book is a drawing of Kate Moss in that white Calvin Klein string bikini. Ali, the book’s teenaged narrator, becomes fascinated — unhealthily obsessed — with Justine, a girl so tall and thin she looks almost two-dimensional. I put the white string bikini on Justine. She shoplifts it out of a Bloomingdale’s dressing room, wears it when the two girls swim together in Justine’s family’s inground pool, and then again, later, face down in this same pool, dead. Like Anna, I wanted to submerge and kill what was monstrous. And like Rachel, I made a copy of its image.

No, I do not blame Kate Moss for my eating disorder. But I acknowledge the power of her image. Sure, she’s just come up from a quick swim, wringing out her long, wet hair, a carefree girl, so lighthearted she might just evanesce. Or has she crawled up out of my subconscious yet again, hair sopping wet, feet bare, slowly approaching? Coming for me? Grabbing at my ankles. Breast reduction? Inner thigh liposuction.