Things, A Feint

C.M.K

This is how I imagine your morning, the morning you chose for the calls to say he had died. He’d warned me about a call from you. What were you feeling, his executor, his address book in your hand? Do you still covet his silver dessert forks?

You lean your cheek against the window and watch the sidewalk below, where people cross the hard-edged shadow cast by the new tower, the tower whose construction he suffered, your magical uncle. The thought of his complaints returns you to your purpose amidst his things. You’ve kinked the cable from the heavy black Westinghouse phone around the loveseat so that it reaches the dining table. Blue rubber bands lie beside the bits of papers they’d held together: business cards, supermarket coupons, annotated scraps in his increasingly splayed hand. You lift the receiver and begin your calls with the numbers listed at the tab marked:

A

Estate Condition

By 11 am, the Hot ‘n’ Cold cups were almost gone and the paper napkin below the percolator handle was soaked. Someone had pulled the wrong end of the Elmhurst half-and-half into a misshapen spout. The Royal Dansk sugar cookies were gone from the paper plate on the foyer side table.

By 3 pm, the couple in lightweight sweaters had bought the vases from the coffee table, tureens from the kitchen. Four young men indistinguishable in dark jackets, lingered in his bedroom fingering his sports coats. The older people, those who had known him, finished their weak coffee and left empty-handed. His neighbor, the one from down the hall, was last to leave. No one would buy the loveseat where she sat for hours, overseeing the drift of visitors, as if she were at a garden party or christening.

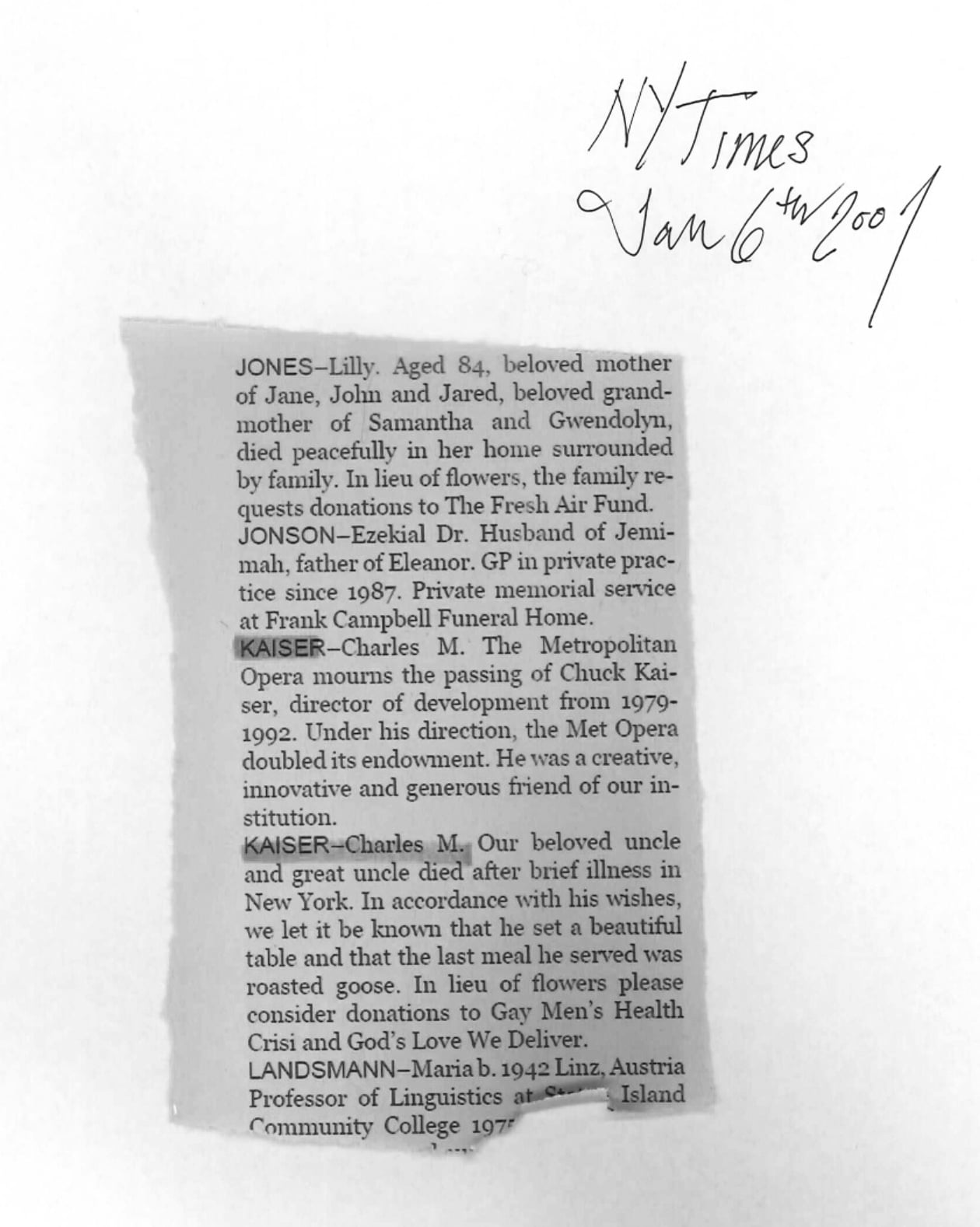

C. had shared her Times. She, the early riser, walked over the dog-eared paper around midday. In exchange, on the Saturdays when the aide from the VA took him to the store, he’d pick up a case of pink grapefruit sections in foil-topped cups they both liked for breakfast. He’d unload his groceries from the cart first, then wheel her things over. She’d thank him and press three or four singles into his hand, in which he briefly, meaningfully, held hers, then she’d watch, door ajar, as he walked away on stiff, gouty ankles.

Friends, word-of-mouth bargain hunters, building residents who’d seen the laundry room flyers: C. would have watched critically. Bargain hunting was a craft lost on the Upper East Side, gone the way of knife sharpeners who rang hand bells as they walked; or the Irish doormen who stopped the knife sharpeners until the housewives, who’d heard the hand bells above weekday traffic, could bring down their kitchen knives. Gone too were the savvy Sicilian fruit purveyors and the building porters who, for a small consideration, could store a double bed in the cellar for an evening, then set up a spare table where the bed had been so that the junior partner and his wife could host their first, lavish dinner party. Value hunting, C. would have added, not bargain, because who wants what merely is cheap?

Item 2: Bronze bust of CMK at age twelve/thirteen, by William Zorach, dated 1939-40. Impeccable provenance.

The train departs Penn Station at 5:00 pm; his dinner seating is at 7:45 pm, between Albany and Syracuse. He’s turned a wing chair in the observation car towards the window and watches the Hudson River. Even as the sun sets behind it, he never loses sight of the water, bounded and directional, like the tracks of his train, utterly unlike the Lake whose far banks he can see only on maps. There are plenty of boys on the train, but he is different. He is not with family. He is alone. He wonders, as the pane of glass before him grows dark and reflective, how this might differ from the trip to New York, the one he’d taken with Uncle Philip.

“I imagine you’re from the Midwest?”

A young man in the chair next to him has stood to leave but, changing his mind, stays a moment longer. C. has seen his contour in the glass. The man wears a narrow-cut jacket in subtle plaid. His reflected torso vanishes where river water catches diffuse evening light and his face is blurred by the bright sconce. C. does not like his question and remains facing the window, postponing an answer.

“No offense meant,” continues the young man, “but it is fascinating to see you watch the river so intensely. Perhaps I have it wrong. Perhaps you are so deeply a New Yorker that you’re trying to forget you’ve left the coast.”

C. smiles at being thought a New Yorker. He’s spent only ten days there, and much of it in the sculptor’s studio. He enjoyed holding still while the sculptor produced a different model each day, roughly molded in reddish-brown microcrystalline wax scraped from hard, bubbled blocks that became pliant when kneaded. The sculptor had given him a small ball of the wax to roll between his palms as he sat. With Billie Holiday on the phonograph, Uncle Philip kept him occupied — he felt like an adult, even if the whole thing felt tedious.

C. explains much more detail than he intended to the young man on the train: his uncle’s gift, his bar mitzvah, his trip to New York and now back to Chicago. The young man seats himself again, drawing his chair closer to C.’s. Albany nears and C. remembers his dinner seating. The young man remarks that his, too, is at 7:45 pm, perhaps they can eat together? It is not often that he has the opportunity to speak to today’s youth, tomorrow’s men.

At dinner, the young man orders them beer. “After all,” he says to C., “as you told me, at 13 you become a man and therefore, man to man, we can certainly share a beer together? As Midwesterners, it’s our birthright, don’t you think?” He flags the busy waiter who asks nothing more than the number of the roomette to which the beers should be charged, and the young man gives his.

The dining car slowly empties and the waiters replace the white linens with red, transforming the space for the rest of the night into Club Metropole. For that, C. knows, he is not man enough. The young man offers to walk him back to his roomette.

“This evening has been my pleasure,” says the young man, proffering a visiting card. C. is chagrined that he has none of his own. He decides to ask his father for visiting cards as soon as he is home. “If we don’t see each other before the train arrives in Chicago, I wish you all the best.”

They have shaken hands and the young man has turned to leave. Again, as he had in the observation car, he hesitates and turns back. C. still stands at the door to his roomette, the key in his hand, waiting.

“May I tell you something, C.?” asks the young man. “It is something that I wish someone had told me much earlier, perhaps as early as the eve of my own thirteenth birthday. It’s something that to this day, many of the people who believe they know me best, many of those who claim to love me most, do not know. It’s something of a secret, something like belonging to a club. Only those inculcated can see it in others, and only those who know it about themselves can take pleasure in it. I believe it is something that you and I share.”

C. is curious and confused. The young man’s gaze, mild and relaxed all evening, seems intent. C. thinks there are already enough people who claim to know him best, those who claim to love him most, and that they have provided plenty of rules by which he is to play: when to do his homework, when to have his dinner, what to wear on each occasion, where he will go to university, how good his French needs be. He wishes for no more dictates. But the young man continues.

“I, at least, know what you are, who you are; I am the same way. You’ll find others. There is no shame in it.” C. looks at the floor and is silent. The young man turns to go, then adds: “Good night, then, my dear friend, and all the best for you. How fortunate for you that, as a bronze bust, your thirteen year old self will be with you throughout your life. Thank your bachelor uncle properly, please, for me.”

Item 28: Print and engraving plate. 5"x7"; copper drypoint plate; framed print. No signature. On verso in pencil ‘CMK home, Chicago, 1927-43; dem. 1959'

The house is on Lake Shore Drive, diagonal to the Drake Hotel, just where the Drive turned inland from the shoreline. Beyond the boulevard, the sand; and beyond that, the blue-grey water he can also see from his window, water pungent with effluent, its reek blown by prairie wind towards the house across the seasons. He sleeps in the turret, below tiny high windows arrayed on the curved walls, and wakes every morning to consider the two geometries overlaid, rectangle on cylinder. His brother sleeps next door in the mansard, square-edged and easier to furnish.

For the cook, the driver, the day maid, the boys’ nurse, the house begins in the side lot garden. From the stoop, the peripheral view includes the sundial, the climbing roses, the espalier apples and pears. There is an ankle-height coal-dust halo in the late-season snow. A heavy back door lets onto the cloakroom with its boot rack and water closet. The house rules are clear: no street clothes beyond this anteroom and even in winter, a clean-swept white Indiana marble floor. A wide door painted glossy cream leads to the cellar, with its wooden bins for potatoes and apples and carrots, its shelves of mason jars sent up from the family farm in Cass County. On the other side of the cellar, carefully partitioned using tongue and groove boards, are the new furnace and the coal. No more scuttles for the maid to carry, but plenty of shoveling beneath the kitchen floor so that the boys may have their hot baths each evening.

One floor down from his turret are his parents’ bedrooms: his mother’s to the right on descent, her dressing room enfilade with the study where she sits afternoons, writing her ledger and journal entries in faint, hard graphite. The doors to her bedroom stand open and he admires how her windows fill with the treetops he can’t see from his turret. His father’s study is at the heart of the house. The new desk, veneered in rippled auburn anigre, has pivoting modern file drawers and leather-lined grooves to hold pencils at the desktop’s edge. Between the ground floor and his parents’, the wide stair is carpeted in deep blue wool. He rarely stops on the ground floor, with its parlors and living room and formal hall, but when he was little, he loved the kitchen.

On turning eight, he asks that his bed be moved to stand below the center point of the turret. From there, he can watch the sky through the five hard-edged windows. In summer, when the sun sets after his bedtime, shadows cross his ceiling. In winter, he waits for headlights from Lake Shore Drive to reflect in weak parabolas around the bend at the Drake. Sometimes snow blown across the Lake catches the light. Sometimes he imagines the lake water fetid below the ice, roiled where thawed discharge flows beneath the frozen surface, along the city’s edge.

Item 5: Boxed set of 24 Anton Michelsen desert forks and spoons in gilded sterling silver and champlevé enamel dated 1927-41 (1940 spoon and fork missing)

As with every year, he set a silver fork and spoons tail to tip above each place setting. His table easily sat twelve, although when they’d been a couple, they’d clustered at the end closest to the kitchen. Now he mostly sat alone, his recompense a photo leant against a highball glass: to friends lost. Twelve at his table on Christmas: one guest for each day, as he wrote on his invitations, Repondez S.V.P. It was always a joy, the twelve, gathered around his ivory jacquard tablecloth, a stack of pale celadon and gilt-edged plates at each setting: entrée, salad, saucer, soup, bread-and-butter, a tiny salt cellar and silver-plate pepper mill. Dessert fork. Paired spoon.

The first fork and spoon had arrived just before his first birthday, by subscription. The last came the Friday before Pearl Harbor, his mother’s joy at the openwork leaves and pin-prick globes of white enamel mistletoe undeterred by the somber atmosphere. Her tenacity, ordering the silver throughout the Depression, was outmatched only by the declaration of war. What, he recalled his father asking, did a Jewish family in Chicago need with Danish Christmas silver, under the circumstances? Under any circumstances, truth be told? She offered no answer — then did not speak to anyone for several days thereafter, not to her boys, not to her servants, certainly not to her husband.

C. understood her protest. He also loved the packages that arrived each December, as snow grew into banks around their front steps and the ride home from school each day grew darker. Each pair, fork and spoon lay, husband and wife, in a rosewood box lined with green pigskin and bound by a red silk ribbon. They opened the packages together, he and his brother and his mother, each year’s motif revealed to them all at once: the silver child holding a silver sash beneath the towering Cloisonné fir, a hooded figure with a star-engraved cloak and three etiolated red petals that might be the flames of her lamp, three tiny winged swallows caught in a grille-work of thick, ripe wheat heads. He most loved the handles, identical to fork and spoon, that inspired stories he could imagine completing. He’d sat for hours, it was 1934, in the darkening dining room, wondering why the ram’s head rested on a stool at the right edge of the tiny smooth rectangle that might instead have framed symmetrically the haloed Madonna and infant, his tiny head crowned in a halo no smaller than his mother’s. Was the ram like Jacob’s? Was it a manger ram, like the one in the school Christmas play? He liked the ram, peripheral but part of the scene, aligned with both his versions of God. When he told this to his mother, she had the maid put the spoon and fork away. Garish 1940, an uneven six-pointed star cut into the handles’ end, gold tines and bowl, was his least favorite.

Alas it was 1940 that his grandniece slipped into her pocket. She was seven, his age when he’d lost himself with the ram. The theft left one rosewood box empty. And although he chose to be patient, her crime was never outed. She grew into a woman difficult for him to forgive: beautiful, competent, indispensible to him in the end.

Item 38: Dachshund Statuette with Corkscrew Tail. Bronze. Stamped Israel. Corkscrew tip blunted.

A poor man’s Auböck, C. had laughed when J-F chose the bronze dachshund from the case. Their guide was outside finishing his cigarette, leaving them a rare moment of discretion. It was unaccustomed, two men traveling together this way. It disrupted the usual tourist itinerary: a rose window, a bazar, the casbah, the Corniche, the silversmith, the tannery. Something for him, something for her. But for him, for him?

J-F turned the dachshund over so that its corkscrew tail sat between his ring and index fingers. Its short bronze legs jutted from his palm. Your tribe, he laughed at C., look at who makes poor man’s Auböck. There it was, embossed on the dog’s flat belly in two-millimeter letters: ISRAEL. An interloper, said C., a well-placed disruption. Or a spy? asked J-F. A refugee in need of rescue, C. averred, taking the dog from J-F and passing it to the shop attendant who stood beside them, his hands clasped behind his back.

C. took in the rest of the shop’s bronze objects: a crown-shaped dish, the gaps in the crenulations tapered to hold a burning cigarette; a truncated foot to hold down stacks of loose papers; a bottle opener shaped like a pilgrim’s fish and studded with turquoise, its tail beveled to pry off cannulated beer caps.

Is there more, C. asked the shopkeeper. Their guide had entered the store. He cleared his throat, ready to move them on, concerned that business be divided amongst all the shopkeepers who subsidized his services.

Just tell the man to send it all back to us in New York, said J-F with a gesture that left unclear which parts of all he intended. Most certainly the dog, he added, that one reminds me of the little wirehair you had when I met you, the one you fed ground beef from that butcher who survived Bergen-Belsen. J-F turned towards the door. Wasn’t it grilled sardines next on the agenda, somewhere on the Corniche, he asked, then the silversmith?

The guide nodded assent. C. pulled a business card from a leather etui and laid it next to the bronze fish. We’re at the Bristol, he said to the shopkeeper. My home address is on the card, please have all this – the circle he drew with his hand was no more definitive than J-F’s – sent to that address and bring the bill to the Bristol. Amin, he gestured at the guide, Amin will make sure you are paid. Amin nodded and exchanged an uninflected gaze with the shopkeeper, who was slow to get the drift of things. J-F laid his hand on C.’s left shoulder. Then we can go, said J-F, now that our business has been transacted. I’m hungry.

Amin and J-F already stood in the sidewalk’s white light, but C. paused at the shop’s threshold. He turned back to extend his hand, palm up, towards the shopkeeper. I’ll take the little dog with me, he said, it’s impossible to eat sardines without a good bottle of wine. We’ll need his help with that.

Item 98: Four oak card catalogue drawers filled with unused greeting cards, ca. 1975-present. Filed by event, age, gender: birthday, thank-you, get-well, best-wishes, holidays, blank.

For all his love of social grace, the Hallmark store Fifth Avenue, the one near Brentano’s, had charmed him. His collection had started, harmlessly, when he’d decided to buy a card but forgotten the gender and age of the child to whom it was owed. The cashier made no comment as she rang up the stack of birthday cards he bought to cover all possibilities. He left with a tiny red shopping bag carried on two fingers. Greeting cards, he realized, were ideal, less imposing than engraved stationery, more considered than the postcard.

His parents had written only on monogrammed stationery from Tiffany’s Fifth Avenue. His father’s was dove grey with steel grey borders; his mother’s, ivory, tone on tone; both, with discrete, embossed monograms. Small stacks of envelopes, sorted by color, waited on the newel post each morning for the postman.

His own Tiffany notepaper arrived just before his Bar Mitzvah. It was pale blue, edged in anthracite, masculine but also youthful. He’d run his finger against his monogram in mirror image, raised on the verso, before he wrote each thank you that good manners demanded. All those notes had honed the nib of his new fountain pen. He never tired of seeing his hand registered in the uneven flow of pale India ink, and he never gave up writing that way.

His mother spent afternoons at her desk, the drapery drawn against glare off the water. He’d round the stairs, stepping from thick carpeting to oak floor, then catch her silhouette in the corner of his eye. She was never paused in thought, never distracted by her boys running up and down the stairs. She wrote her notes in fine pencil strokes, the same strokes she used for the vitriolic diaries he would reread one final time upon his seventieth. He could think of no one they’d interest and as if in response to that thought had torn the first page from its binding once he was done reading. He read the next page carefully and then tore it, too, from the book. By evening the floor of his bedroom was littered with pages. If only, he thought, things were as they’d been when he’d first moved to New York, each building incinerating its own trash, transforming it all to soot blown across the city.

After that first trip to the Hallmark, he began to buy cards everywhere he went, in anticipation of occasion: in Montreal ‘bonne anniversaire’; in Vienna ‘Guten Rutsch’; at St. Mark’s Books and Rizzoli’s. Shoeboxes were his practical solution to organization, the cards partitioned into categories by scissor-trimmed shirt cardboard printed in ballpoint.

J-F hated the shoeboxes. When the card catalogue was decommissioned at the library of the school where he taught, he carried home the oak drawers. Together, on weekends spent in pyjamas at the long dining table, they transferred the greeting cards over, rewriting each category on oaktag in clear block letters.

Item 33: Bucks County Landscape Painting, 19" x 25", oil on canvas. Possibly William Langson Lathrop. No provenance. Purchased at yard sale near Windveldt Farm, 1992.

Late spring and early summer were marvels that year. Fields sold to gentlemen farmers ignorant of soil or seeds or sowing but gifted at reaping dividends and capital gains, these fields produced every valance of green, white, pink of their own accord. The warm winter or the wet March, perhaps. Whatever its cause, the landscape was lush.

In Doylestown, the museum responded by hanging Impressionists in its dark galleries. The museum was housed in an old fieldstone jail and its tiny windows channeled the bright outdoor light. But the light in the canvases was diffuse. Tiny strokes of oil-suspended pigment rendered flora, mimicked dappled sun, or so the gallery wall text claimed. But there were more salient things to consider. Bucks County Impressionism was literal and detail-preoccupied. Charles Morris Young painted his home as a realtor would photograph it, from a viewpoint that showed its arced formal foregarden and classically-inspired portico. Fern Coppedge painted en plein air wearing an infamous bear-skin coat, daring! But her bright houses sat within obvious compositions, their gabled roofs and rectangularly framed windows in diagrammatic perspective. There was something in it all more crass than naive. Faux Folk, J-F had judged it, barely Modern.

What were the chances, then, during that magical spring and summer, of finding a worthwhile Impressionist at a garage sale?

Two arced ruts converged in the painting’s foreground, drawn across a verdant field of tall grasses by wagon wheels. Everything swayed in the arrested breeze. A valley beyond sat within the equator of shadow while the upslope rose in full sun to meet the white-streaked sky at the horizon line. Between foreground and middle ground, a figure, dark and near-amorphous, moved towards the sunlight. Perhaps the painting’s only flaw, obvious by contrast to the burst of late spring polychrome around the garage where the painting lay amidst old garden implements and National Geographics, was the cropped red barn or silo. Its form and color were ham-fisted.

They brought the painting back to his cottage. C. was gleeful. But the modest house had neither space nor affect for it. In the end, it hung in the city, where it became totem, not memento, of that spectacular season. He wondered, was it self-flagellation to keep it there above the loveseat, after the Bucks county house was sold, after J-F was gone?

Item 102: 38 wooden suit hangers in polished cherry with cedar inserts. 4" in width at shoulders, standard 11" length. Brass and cherry clamping mechanism for trousers. ‘Italia’ on back face.

The arc of adulthood aligns neatly to the arc of desire for clothing: in youth, clothing is a land of make-believe, an aspiration; at mid-life, it has become habituated; and as age becomes undeniable, an elegant suit offers reprieve, hiding the consequence of slowing metabolism and atrophied musculature. By old age, though, pretense is gone. A beloved moth-holed sweater, wide-legged flannel pants held by a looped drawstring became acceptable, even when company came. But I will always remember him as dashingly clothed, vivid Izod shirts and pressed slacks. Silk ties coordinated with his bright pocket squares. Lapel pins, tie tacks. The ruby signet ring.

I was shocked by the rapidity with which his well-founded vanity disappeared. He had been a spectacularly beautiful young man, remarkably handsome still when he befriended my mother in the late 1970s. My judgment is not skewed by fondness. The photographs he kept in silver frames and in leather-bound albums, each spine labeled by year, attested to his remarkable good looks.

Our dinner dates began after my mother’s death. He never failed to serve a soup course, a salad course, an entrée and then at his behest, I’d set the four or five near-empty pints of ice cream or sorbet onto the table as dessert alibis. Darling, he’d say when we’d finished, pull the album labeled 1950. I might have prompted his nostalgia when I sent a postcard from a trip to Chicago. Darling, he’d repeat as he opened the album, have I ever shown you our first apartment? It was spectacular, a penthouse with a two-story living room, a walnut library, a dressing room paneled in mirrors, a remnant of an untenable moment from before the first War and the highrises. There we were, two young men all the way at the top, a view on one side to the Miracle Mile, the Lake on the other.

One evening I told the story of my friend whose great-grandfather had commissioned a house from Louis Sullivan, the architect who first tried to convince the world that ‘Form Follows Function’, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright called ‘lieber Meister’ even after he’d taken Sullivan’s clients. The house was no hedge to tragedy. Mental illness and disease shattered the family and the great-grandfather moved East to found a new family, the one from which my friend would emerge.

You tell that Chicago story so well, C. said, and you a New Yorker. But when you tell my story, darling, he’d added, make me this promise. Promise to keep me clothed for propriety’s sake. But, he smiled as he said it, drop a subtle, subtle hint of how much, with the right partners, I enjoyed my nakedness.

Unnumbered Item: 16" cast iron skillet. Well-seasoned. ‘USA’ stamp on underside of handle.

For one week each summer, C. visited T. and her husband at their house near the beach. C. rose late, after T.’s husband had bought the newspaper and bagels, after T. had left for tennis and the house was quiet. He’d cook his eggs, make his coffee. “What a mess he leaves!” T. complained. Then he’d head out to the garden with the paper. Propped on a lounge chair, wearing vintage aviator glasses, he read the paper, starting always with the obituaries then moving systematically to the front page. Using the small pelican-handled sewing scissors that traveled with him, he snipped articles of interest he’d enclose in the notes he wrote each afternoon. Once, in gratitude to his hosts, he pruned the wisteria. “Pruning is a euphemism!” T. complained after his departure. “It will take years for that to grow back. It was amputation.”

T. had two grandsons. When the younger visited her, which was infrequent, she made him lamb chops. Their long rib bones protruding from the round eye of meat at the center of the plate, the chops were no less than T. telling her grandson, “I love you.” T. told the story this way: she asked the boy what kind of lamb chops he preferred, her special ones, or the ones he ate at home. The home ones, he replied, the thick stripes of meat and bone a challenge to eat. “I spend money on rib chops,” she ended in denouement, “and he prefers shoulder! Will he ever understand the good stuff?”

C. let slip to me over dinner that she’d told him the story, too. He never succeeded in assembling around his table all of T.’s remaining family, such as it was. But the younger grandson, my boy, loved C.’s dinners. He begged to arrive early, to stand in the kitchen on the pressed-steel step ladder, to watch C. make lamb seared with butter in the iron skillet, seasoned with lots of salt and pepper, then finished in the oven until the timer – “It looks like a laying hen!” my boy told me – rang out loud.

Last Night

Daylight ends early, earlier still now that the new tower obstructs the only window that once caught alembic late-day sun. January is the start of a miserable season. January is the month when people die — the statistics prove this. This is the last January his things will reside where they spent 40 years.

Ciphers of light thrown off slick facades, black with freezing rain, reach the foyer. His magpie taste is there, in the silver and black kitchen wallpaper. The sheen has held up decently against the layers of animal fat atomized to make brunches and luncheons and multicourse dinners. It reflects streetlamps wall to wall, silver to silver. The light is trapped, too, in the water glass left in the sink.

A last stack of flat corrugated moving boxes leans against the wall. Pale fields on the plaster walls mark where his paintings hung. In the streets outside, freezing rain is becoming snow and the first blizzard of the still-new year is laying the city low.

The corner window overlooks nondescript towers that have replaced the masonry tenements that still stood when he was still new to the place. Tomorrow the super will return for the dining table no one else wanted, a gift from the executor. This is what 40 years leave behind: the wallpaper, the yellowed track lights, the heavy, hairy path of grease on the ceiling above the range, the mismatched hot and cold taps, the fractured tiles where the bathtub leak was repaired, more or less. The new owner will order demolition before a permit is issued. His dining room wall will buckle, his mirrors splinter, and the silence of this last evening will prove to be nothing, a feint.