The Beauty of Impermanence

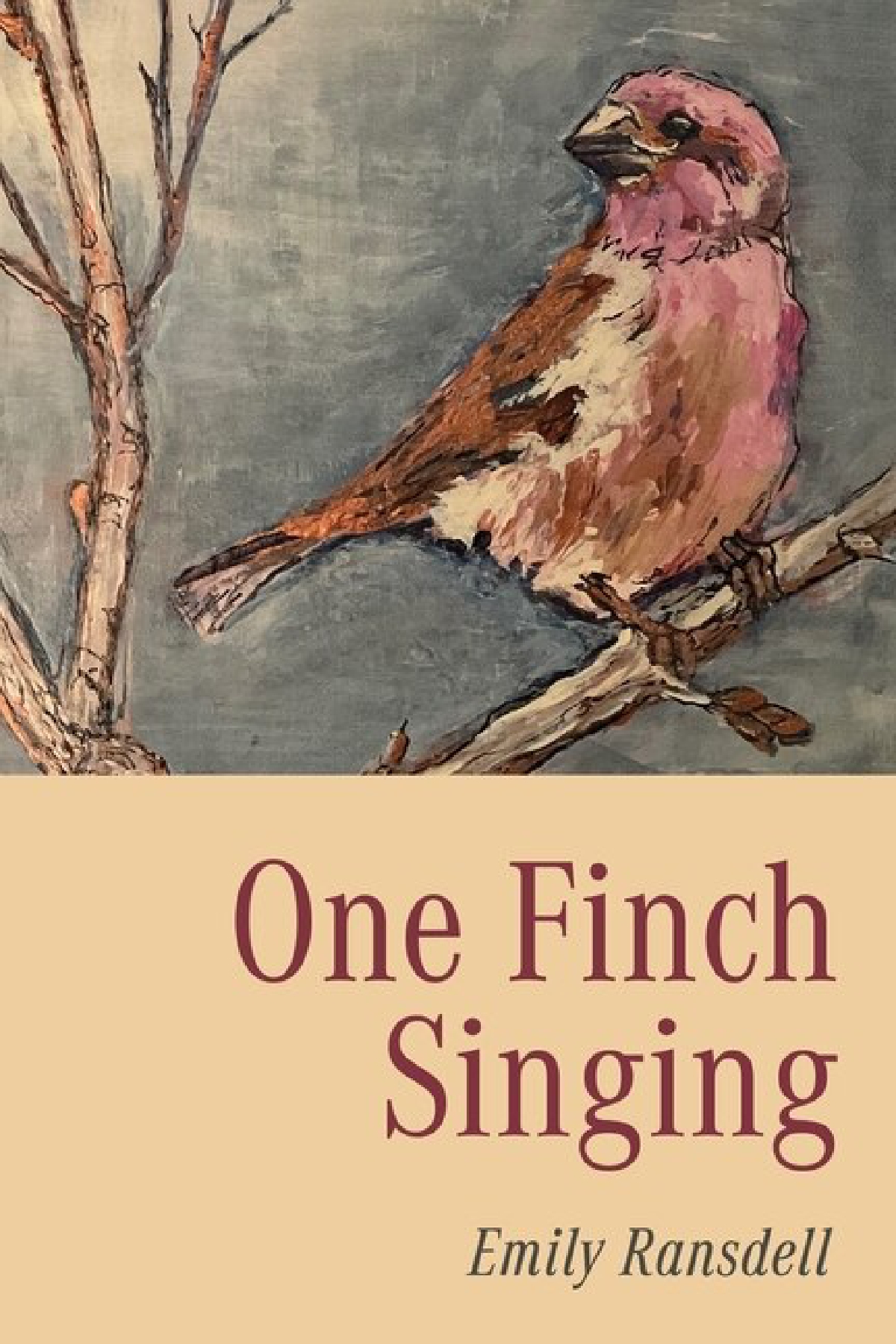

“Absence,” Emily Ransdell tells us in her collection, One Finch Singing, “is like holding someone’s heart in your hand — dense and heavier than you’d expect.” In poem after poem of this remarkable debut, Ransdell teaches herself (and in turn, us) how to prepare for inevitable absences — how to forgive and grieve the loss of parents, of friends, of our innocent hopes that tragedy and illness will somehow skip over us and never strike those we hold most dear. “Impossible that such beauty could be dead,” the poet says early on. And while Ransdell is referring here to a red cardinal, frozen in the snow (an image she renders exquisitely), the bird comes to represent the people and things we cling to, even as we fail to fully appreciate them while they are ours. This use of nature and its destruction provides a consistent theme throughout the book, and the poet uses it to continually steer us back to our human tendency to deny the losses we must endure, simply by virtue of being alive.

Her title poem, which begins section two, encapsulates her theme most successfully with its opening line: “Some days I want to fill my pockets / with everything I’m afraid of losing.” Here, Ransdell showcases her ability to sidle up to difficult subjects, using lyrical language and leaps of thought that surprise. “I read that finches can live on thistles,” the poet tells us, “as if to say, There’s hope.” Indeed, one could imagine a collection that thoroughly meditates on death and loss might leave us to survive on thistles. But instead, Ransdell offers us hope and genuine connection. She does this throughout the book by juxtaposing nature’s beauty with various catastrophes, and by extension, human beings with our inevitable decline. Both nature and humans are made all the more beautiful in these poems because of this impermanence. As such, even as the poem “One Finch Singing” goes on to explore the aftermath of a friend’s death, the poet never falls into despair. “The ancients thought finches carried souls to the afterlife,” Ransdell reminds us, “and the sound of one finch singing meant an end to grief.”

Grief itself seems to be one of the things the poet gathers into her pockets and preserves with these verses. As the collection unfolds, as Ransdell’s speaker weathers the loss of complicated relationships with her parents, witnessing their slow demise, one can see a quiet strength building within her, a strength called upon when a life-threatening illness strikes her own husband. It’s as if the poet has been preparing herself for decades, building the capacity needed to protect and nurture the person she cannot imagine living without. Section three begins with “Beloved.”

Beloved

Bring me your fears. Bring them like a handful of sad white lilies. And your sorrow, bring that too, in the walnut box your father made as a boy. Corners tightly dovetailed, brass-hinged Heartwood varnished to a sheen, treasures you left there decades ago still rattling inside. Dust-colored sparrow wing, a cuff link, the home address of that boy at summer camp you couldn’t save. Bring me the memory of your high school sweetheart, the field behind your house, the long minutes you breathed for your mother until the ambulance came. Bring me your misgivings. Your heartache. I’ll haul it all to the river in a cart strung with white carnations and won’t ask that you come along. You never did like to talk about what’s gone. That’s okay. I’ll come back with that cart scrubbed clean.

As a contrast to the more narrative poems comprising the book, “Beloved” sings with a lyric intensity that drives the collection towards its powerful conclusion. “Bring me your fears,” Ransdell’s speaker tells her partner, as if to say, I’ve waited my whole life for this moment. To gather up all of your memories, the lovely and the frightful, everything that has made you into who you have become. I’m strong enough, now, to carry all of it. “Bring me your misgivings. Your heartache.” And just as this poem promises to haul away the lover’s pain, and come back with the “cart scrubbed clean,” Ransdell in her collection extends a compassionate hand to her readers, inviting us into the specific details of her life, and the lives of those she loves, so that we better understand our own.

One Finch Singing reminds us why we come to poetry in the first place. Poetry seems uniquely positioned to provide comfort during difficult times, and Emily Ransdell’s debut is a collection you will return to, over and over, for clarity and perspective. To be reminded of what is at stake in the passing of each day, “bring me your misgivings,” the poet implores, “Your heartache.”

One Finch Singing is available now from Concrete Wolf Press