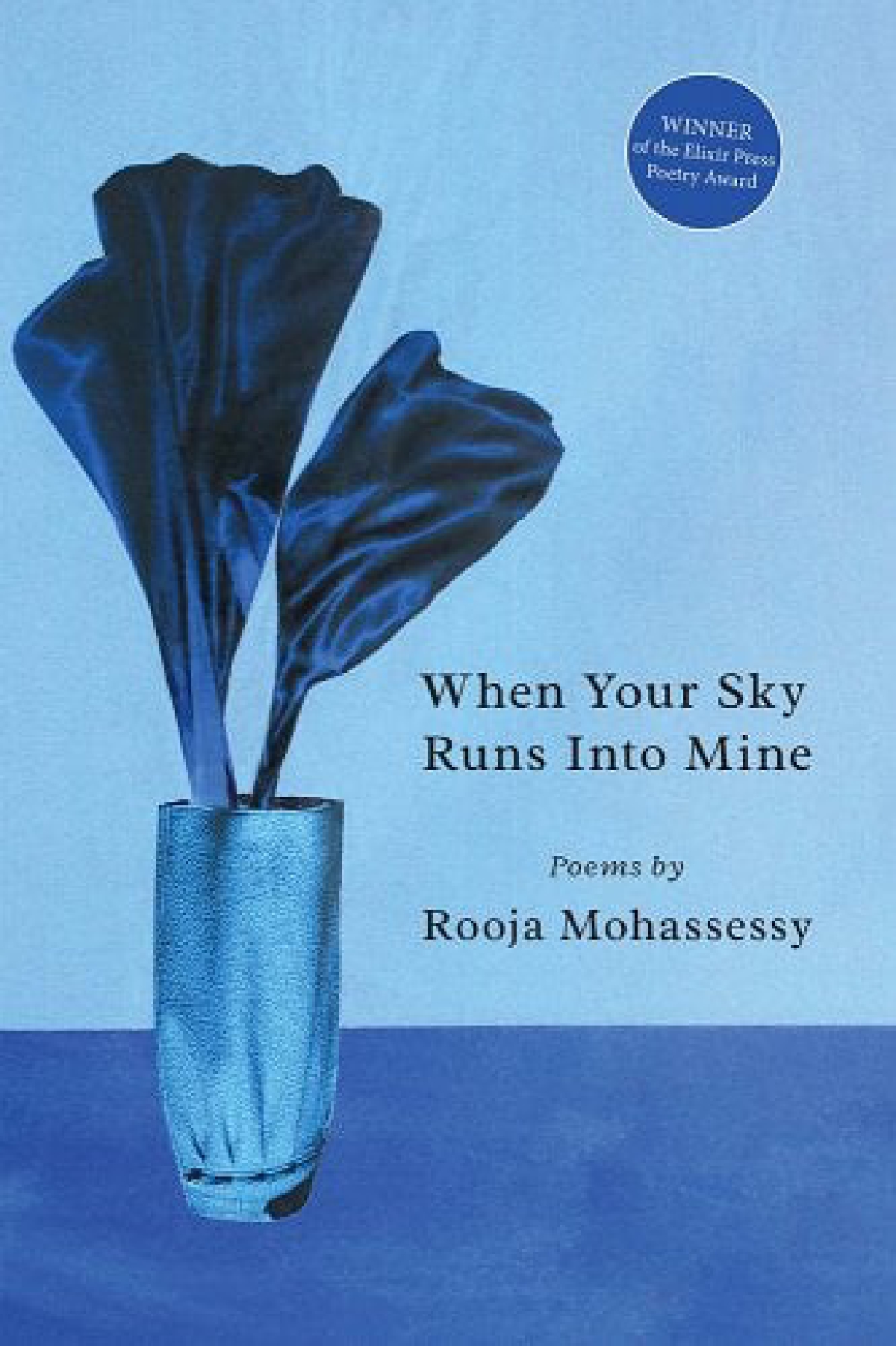

When Your Sky Runs Into Mine

Rooja Mohassessy’s stunning debut collection, When Your Sky Runs Into Mine, arrives as women-led protests in Iran continue in response to human rights violations and the denial of individual freedoms. The poems unfold as “memoir in verse” and begin with Mohassessy’s early memories of a post-revolutionary Iran, where the poet was born. Through these deeply genuine and fervent poems, we sense the profundity of the times, a girl coming of age during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980’s, and the experienced trauma of war and emigration. Gradually, the poet draws the reader into present time although there is no resolution in sight other than the claimed identity of a woman and the inheritance of her ancestry.

Throughout the collection, Mohassessy employs ekphrasis, and from the works of Shakespeare to the song lyrics of Dire Straits, Mohassessy culls from sources of literary and visual art — Gone with the Wind and Rembrandt’s Danaë for example. Many poems were influenced by the artwork of Mohassessy’s late uncle, Bahman Mohassess, a prominent Iranian modernist painter and sculptor. Before his death in 2010 most of Mohassess’s art was destroyed, much of it by his own hand or at his orders, in an effort to keep it from falling into the hands of the Iranian government.

In Mohassessy’s opening poem, “Iran Politics in First Grade”, she describes an early impression from the television news. People “like swallows on a downed / powerline” as they tied a rope around a statue’s neck. Through the eyes of a young girl, the images of the anti-Shah demonstration projects onto the future like prophesy.

Next, we see the poet as a schoolgirl, her head and body covered by a hijab. We hear the foreshadow of her inner thoughts, “It’s time to come to terms / with the dark.” In adolescence, a time when “stoning came in vogue”, Mohassessy recalls the public lashings and sexual assaults by guards while the morality police are more concerned about enforcing their ideology. Perhaps there are implications of complicity to consider? Hypocrisy is amplified by references to western culture – Hollywood, dance trends (both Persian and Western) and certain global commercial brands. The assault on women continues for half a century (the poet is witness) while around the world, commerce and the consumption of culture continues. Women pay the heaviest price.

With imagery and language, Mohassessy signals of dangers ahead. A “glowing list of God’s mandates” emerges as black cloth, “determined to accompany us out of doors.” Yet there is no protection for women in war. In a poem titled from a quote: “They Were Blind and Mad, Some of Them Were Laughing. There Was Nobody to Lead the Blind People”, a deep vulnerability sears through the horrors of chemical weapons.

In “Spared”, Mohassessy demonstrates how manipulation and lies packaged in deception mercilessly progress from belief into doubt. “Even the outage is for our benefit,” and “we recount /those lies that comfort us”, precede the deeply repressed yet emerging fear. “We talk of stockpiling / potatoes, though it’s a sin to be so frightened.” But, how, Mohassessy seems to ask, are they not to be frightened by orphans and limbs, a depth of grief “we measure / there the neighbor’s catastrophe–/ the circumference of her wound.” In contrast, Mohassessy isolates purity and innocence with a single image: a child uttering reverently (in Farsi) the names of family members and loved ones, that they might be spared.

Where ekphrasis is not always detectible, the outcome is a deeply personal, lyrical narrative. The book is dedicated in memory of the uncle whose presence graces these poems, as do other members of Mohassessy’s family. Her mother and father, both of whom are deaf and mute, and also Mohassessy’s sister, aunts and maternal grandmother, to whom the book is also dedicated, along with the courageous women of Iran, “its true warriors.”

By her interpretation of her parents’ experience, it is possible for Mohassessy to articulate a shocking silence inside the loudness of war– it is not a peaceful, restorative quiet, however. In “Rose D’Ispahan” the relationship between the young daughter, who is her mother’s interpreter, and the dependent mother is revealed. In reflection, the grown daughter asks, “Who signed the air-raid siren / into your eyes? You managed though the house no longer heard / the doorbell, could barely read or write, every room dumb, / half-opened doors shutting without a sound.” In “Believers”: “my mother couldn’t hear the night sky / rip into starry strips, she felt the warheads rumble, / listened with her feet / she kept flat under the table.” And in a poem named for Mohassessy’s father, she speaks his name, Siavash, and of women’s prayers– how they “would’ve laid their lives at her feet / to awaken the dead drums of your ears.”

From “War of the Cities”, more silence:

We wear our day clothes to bed like soldiers, lie semi-propped up, a flashlight sinks into Leyla’s pillow like a doll, deaf and dumb, our parents move blindly about the house, what senses they have, honed, the sky overhead resigned. Starless. In the small hours — I daydream of heaven — Mamman, Baba with Leyla, my palm in Madar’s, we rise out of an immaculate ruin, against a backdrop of hellfire, flanked on both sides by fallen martyrs, their blood scabbed into fields of poetic poppies that die at the vanishing point…

With no possible reconciliation of the two worlds, sometimes the only place to turn, it seems, is to the absurd. However, where the poems should bite, they do. Other times they are tender, erotic even, as in “Eggplants”, a poem adding humor to nuance. Language fails only when Mohassessy wills it to, as in “A Muslim”, as her mother, during a video chat, shares her anguish over the news of a suicide bombing committed by Muslims. The poet abandons language, choosing not to relay the details of the report, the retaliation, or involvement of religious extremists, etc. Instead, she lifts her little dog, Fifi, up to the screen; all she can think of to ease her mother’s grief. It is simply so realistic that a poet may relent, especially when the conflict and struggle is unrelenting.

The trauma of forced displacement as the result of war lingers in Mohassessy’s imagery. Racism, xenophobia, and psychological impacts are addressed in the poems, yet it is surprising how delicately the poems tread given their thematic weight. Mohassessy’s poetry captures more than one perspective, including the persistent and troubling discrimination and violence against Muslims and immigrants to the United States.

In “Native” the poet writes from her California home:

Let us toast and feel the draught rip our throats, hit the same gnawing spot we share in this scorching twilight; it seems no ordinary drink will wash away our animosity, each hunkering uninsured at home in the heart of the High Fire Hazard Severity Zone where you stand and brandish your gun, the American flag leaning to take a strike at the air beyond your deck.

In “Bared”, a California holly shrub conjures the Muwekma Ohlone, the first people of the region. The birds feast in the back-alley brush where the doe, “the high priestess of the woods wavers”. Even in this most unlikely place the poet senses a junction of two worlds. “Come nightfall, / creatures shall shiver like stars, stare unblinking into the blackness now bared / and leveled. / I keep vigil– my home lit up loud as a blunder.”

The art that inspired Mohassessy’s poetry is posted in a gallery online. Here, you can see the mixed media piece by Bahman Mohassess that inspired When Your Sky Runs Into Mine. It is an image of a crane and a bison, an unlikely pair, standing together in a field beneath a bright blue sky. Mohassessy’s poem, in the same way, speaks to apparent differences and their insignificance. As endangered species, they are equally at risk of peril regardless of ideologies inherited, or otherwise.

You can view the works of Bahman Mohassess in this online gallery: bahmanmohassess.com.

Rooja Mohassessy is an Iranian-born poet and educator living in Northern California. She is a MacDowell fellow and a graduate of the Pacific University MFA program. Her first poetry collection, When Your Sky Runs Into Mine, was the winner of the 22nd Annual Elixir Poetry Prize and will be forthcoming from Elixir Press in 2023. Her poems and reviews have appeared in Narrative Magazine, Poet Lore, RHINO Poetry, Southern Humanities Review, CALYX Journal, Ninth Letter, Cream City Review, The Rumpus, The Adroit Journal, Bare Life Review, Potomac Review, The Florida Review, New Letters, International Literary Quarterly, and elsewhere.

When Your Sky Runs Into Mine will be available February 1, 2023 from Elixir Press.