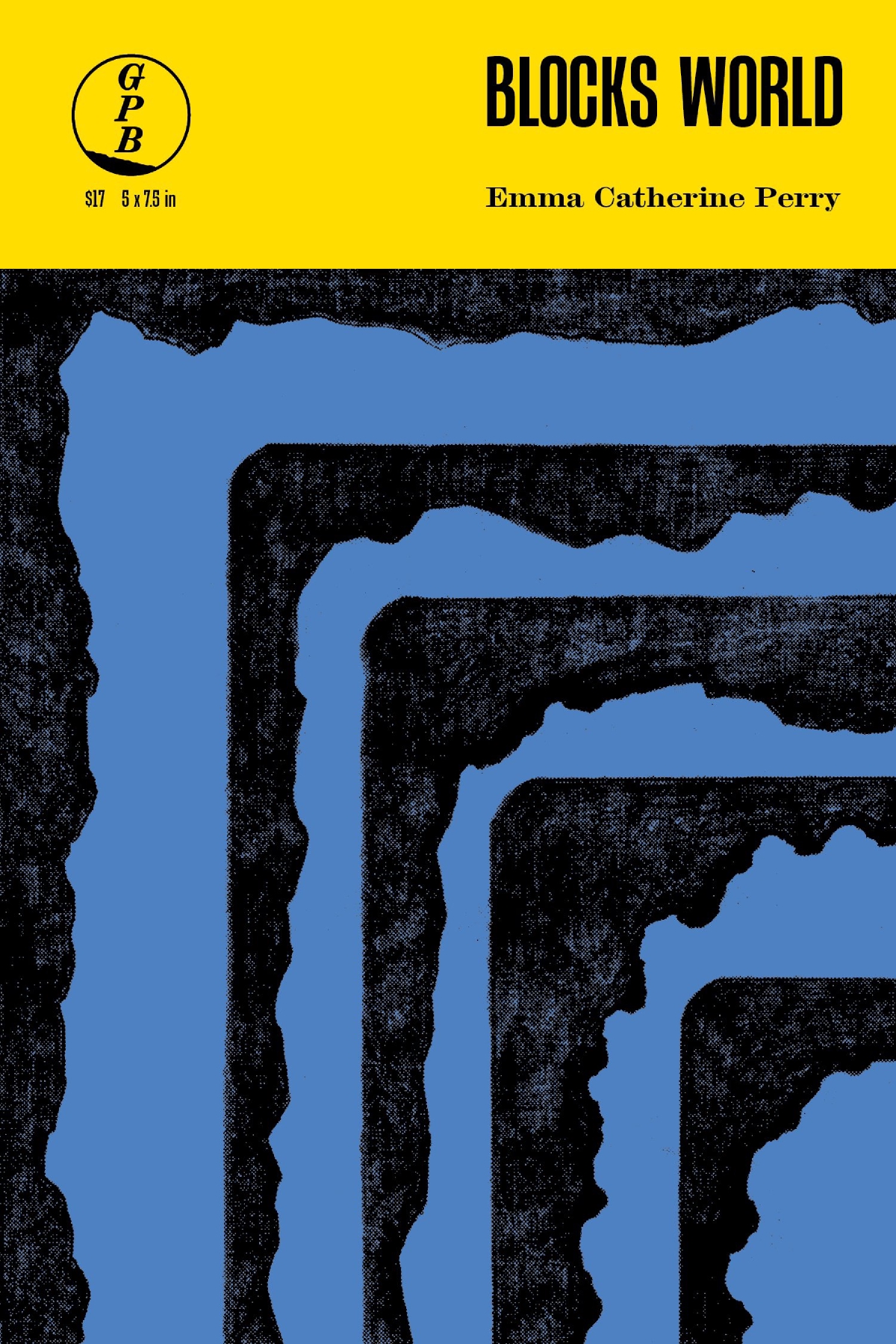

No Love Without Pain: Emma Catherine Perry’s Blocks World

Timeliness may not be a virtue often associated with poetry and all its connotations of immovable sublimity. Nonetheless, Emma Catherine Perry’s debut collection, Blocks World, could not have come at a better time. Preoccupied with computer science, the collection is an aesthetic contribution to the ongoing discussions of artificial intelligence. Intelligence, artificial and otherwise, is already a nebulous concept, and in Blocks World, it receives an especially skeptical treatment:

Every scale in perfect imbrication as though it were possible to build an answer out of existing blocks of knowledge

Mind is a wall of leaves that looks solid and then a bird flies through

Artificiality, intelligent and otherwise, is already a contentious mode, and in Blocks World it plays an especially ambivalent role. The poems are highly formal, using computer science jargon, and sometimes sprawling across the page in geometric configurations. Yet thematically, the poems insistently challenge the value of invented things:

when the computer wants my attention it sounds the chime that signals its want when the sword fern wants for nothing it slowly lifts its arms.

Epistemological concerns are only a portal to spiritual turmoil, however, and the collection’s deft lyricism deserves praise. Its language is playfully precise, demonstrating a rhythmic and idiosyncratic syntax that puts one in mind of Gerard Manley Hopkins, to the extent that at first glance, certain lines are impenetrable, yet upon being read aloud, transform into self-evident incantations:

the fledglings maw their pinkling gape bedraggled as all get out the nest.

That verbal sophistication never impresses as performance, but rather eschews mere virtuosity in favor of an earnest voice, which must only be the result of a lifetime’s honing. Not stooping to trifle, Perry’s style remains subdued in service to the themes of her collection; themes roiling with longing, frustration, and a sometimes removed scorn for the speaker’s anguish.

The collection is organized into five subgroups of poems: “<>,” “Blocks World,” “Cluster Analysis,” “Download.Doc,” and a grouping of individually named poems. Some poems are formed as dialogue between speaker and computer, a dialogue mutually frustrated by an encompassing inability to comprehend the other’s frame of reference. The mood is one of alienation, a predicament compounded by the addition of a third party — the natural world. In fact, all three “Blocks World” poems are named after a non-human organism: “The Lobster,” “The Pea Plant,” and “The Octopus.” The speaker(s) in the poems yearn for insight into the motivations, experiences, and perceptions of their organic subjects, compelled by the vain hope that they may deduce a sovereign remedy:

What does the pea plant know about pain may I ask if I speak quietly? I want the pea plant to demonstrate a truth about myself

Yet the collection does not once indulge in resolution. Its speakers are just as alienated from the natural world as they are from the artificial intelligence with which they collaborate to build the poems. An important and excruciating distinction is that though all three parties are ignorant of each other, only the speaker is mystified. Said lobster may or may not feel pain when boiled alive:

the scientists say it isn’t humane though they cannot say whether the lobster feels pain

Failing to see the speaker’s predicament, the computer often reacts literally, or with confusion, prompting the speaker to exclaim, “I swear to God if I could do this without you I would.” That expression of frustration is a reduction of Blocks World’s central conflict: trying to live without getting hurt by the most volatile variables in our emotional world — other people.

The speaker laments the impossibility of being both invulnerable and connected: “I wish I knew how close to be.” Perry provides something like an answer. In “Download.Doc II,” a second person poem whose addressee is unclear, Perry writes:

If I continue to stand with my back to the world, I am weighing the choice of the choice there is another life beyond your life and another life beyond

Those lives beyond our own — the little brown snake with her “lick of intelligence,” the ants and the beetles in “a network so dense”, or a father who is “a mountain” in your life, and perhaps even the disembodied intelligence you wish you could do without — they are to be faced. Though they are mysterious, and often dangerous, they are indispensable to doing this. For as Blocks World tenderly demonstrates, we cannot live without being alive.

Blocks World is available now from Great Place Books.