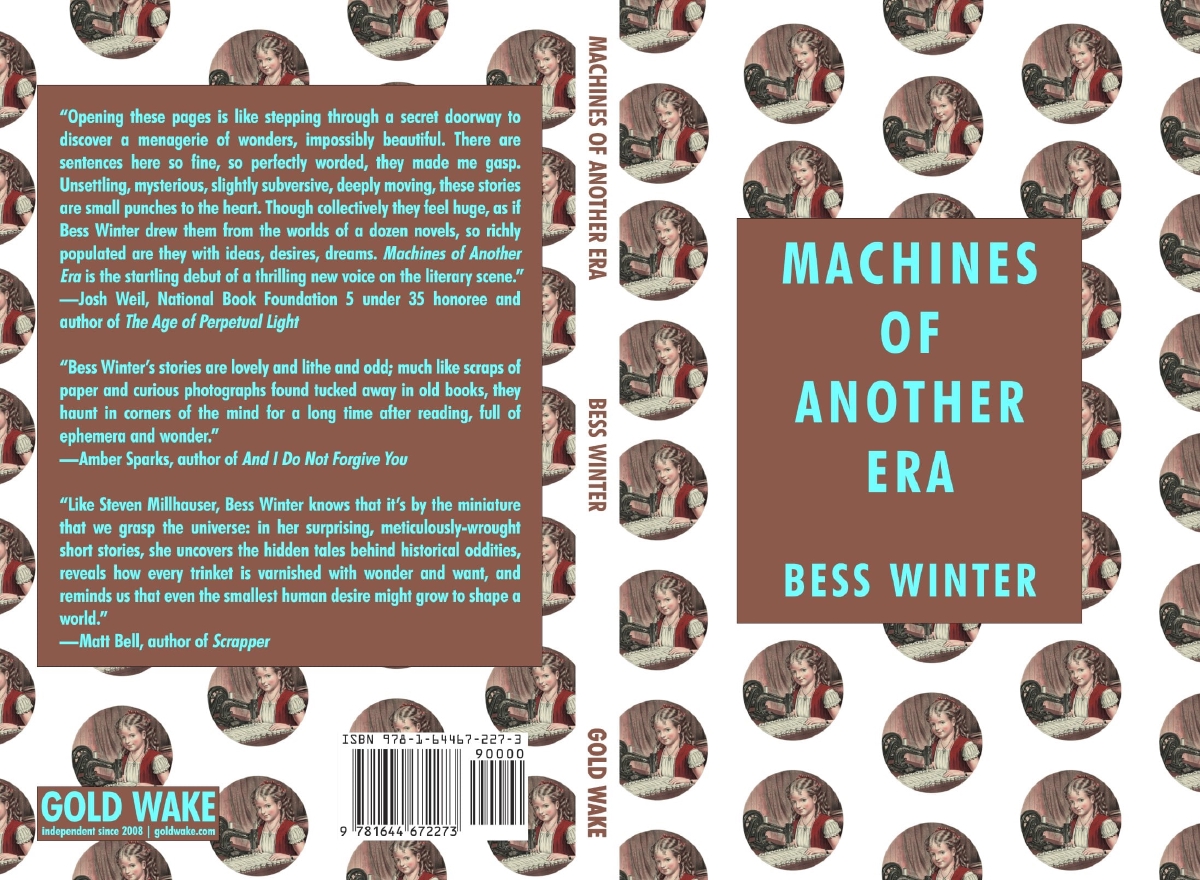

Machines of Another Era by Bess Winter

A few years ago, I found myself scrolling through a listicle, choking up with laughter. Compiled before me were a series of tintypes from the 19th century. Tintypes required long exposure times, so if families and photographers wanted babies to sit still, they had to get creative. The solution? Mothers in disguise. They sat on armchairs, draped in blankets or rugs, so babies could sit peacefully on a familiar lap. The article referred to this as “ghost mother photography,” which sounds spooky, but the drapes were undeniably person-shaped, akin to an elephant hiding behind a lamppost. I laughed so hard I cried.

In Bess Winter’s short story collection, Machines of Another Era (Gold Wake Press, 2021), I encountered these ghosts again. In “Hidden Mothers,” a photographer becomes adept at disguising mothers for tintypes. The story takes a turn when Winter writes, “Several mothers, once he’d cloaked them for a photograph, had confided in Sargent that the disguise might make their mothering easier. A child might never grow to resent the constant presence of a large throw pillow. Might never notice at all.” In a move that’s emblematic of this collection, Winter seamlessly melds humor with heartbreak. The absurdity of someone wearing a bearskin rug makes it all the more disarming when it’s revealed they’re only doing so to circumvent the tumultuous love of an adolescent. I was crushed by the same ghost mothers who once sent me into a giggle fit. Funny: an armchair that’s clearly a person. Not so funny: someone desperate enough to avoid a particular grief that they instead choose to be an armchair. Winter takes curios from bygone days that veer on the absurd — hidden mothers, a crowd eager to try a shop’s first shipment of hashish candy, malfunctioning dolls that screech demonically — and imbues them with pathos, making the past and its characters feel immediate.

The bearskins and drapes and ottomans aren’t the only parents mystified by their growing children in Machines of Another Era. Daughters confound their parents throughout these stories. In the opening of “A Beautiful Song, Melancholy and Old,” dysfunctional father Leland wields a newspaper ad that offers a fifty-dollar prize to the youth who kills the most flies. Leland believes his daughter, Myrtle, is the kid for the job. Set in a bygone Toronto that’s overtaken by this morbid competition, the story follows Leland as he tries his best to buck expectations and be a good dad. His wife and other daughters barely speak or look at him. “Only Myrtle,” Winter writes, “musters the energy to be disappointed, now.” Even the policeman Leland meets outside of City Hall, while Myrtle’s flies are being counted, looks at him askance. As Myrtle’s scowl softens over the course of the story, we can feel Leland’s joy when she warms to him, and smiles “a real smile, no sarcasm. The smile of her little girlhood.” These moments are fragile and slippery, and Leland knows how quickly they can sour. Like in so many of these stories, Winter renders the intensity of adolescence with respect and subtlety.

In “Helena, Montana,” another old man fumbles with his newfound responsibility. Goodyear, a postman, arrives at the post office and finds a baby in his mailbag. She needs a diaper change, and Goodyear wonders whether he should clean her up. Winter writes, “But she’s a parcel? said Goodyear. Wouldn’t that be tampering?” As he walks along his mail route with the baby he calls Helena, he wonders whether his duty is to his profession or to Helena. Many of Winter’s stories answer the same question that runs through Goodyear’s head when Helena first looks at him: “What are you going to do now, strange man?” When the time comes to deliver the parcel-baby to its destination, Goodyear meets “a girl, perhaps sixteen” who baffles him as much as Helena does. Like Leland with Myrtle, the split decision Goodyear makes for Helena will reverberate through the child’s life.

At various points in Machines of Another Era, I was reminded of Shirley Jackson’s “The Intoxicated,” a story in which a drunk man seeks solitude in a kitchen during a house party, only to find the host’s daughter there, taking a homework break with a cup of coffee. The seventeen-year-old is startlingly blunt, causing the man to second-guess his every word. In their short conversation, she reveals with cool certainty exactly how she believes the world will end. In Machines of Another Era, we get a similar sense that the youth know something the adults simply can’t access. Myrtle, and even baby Helena have a certain gravitas that belies their age. In “The Garnet Cave” there’s a secret cave that only children can find their way into. One woman, compelled by the gems’ mystique, follows the children one night and discovers more than just the cave she was looking for. I experienced a surreal moment when I described this story to my partner, and he recalled, for the first time in the decade I’ve known him, how as a child he chipped garnets off a rock face in Maine. Winter has an uncanny ability to reach into the past and show us something that, though long-forgotten, still glimmers.

In these eighteen stories, young girls teeter on the brink of adulthood, filled with guilt and dread. Lonely, strange men make their ways through the world. Children, with their secret knowledge, baffle their parents by growing up. While the stories in Machines of Another Era vary in length, they are threaded together by the looming past, by moments of surrealness that hover on the edge of unreality. The title story features a fictional Gabriel García Márquez and his brother, who reads Márquez his own stories while the ghost of their grandmother looks on. The occasional magic in these stories is refreshing, neither evasive nor over-explained. Winter expertly manages mystery, and doles out just enough description to make the world of each story come alive.

The final story, “The Stories You Write About Mimico,” serves as a perfect end to the collection. Mimico is a Toronto neighborhood, and Winter gives us snippets of its various eras through time. In addition to its compelling structure, it offers a reprise of the collection’s themes. The story opens with Oscar Peterson playing his out-of-tune piano. Told in second-person, it’s addressed to a teenage Bess, who aspires to be a writer and tries again and again to write stories about her hometown. It’s the same Bess, presumably, who will eventually write the collection the story appears in. And just like the writer Bess Winter speaking to teenage Bess, the story itself takes the past and pulls it close. Each narrative thread eventually comes to a scene in which the characters hear the distant music of Peterson’s piano. Time collapses, and the ‘when’ of each thread no longer matters. The final story echoes this collection’s most impressive achievement: it makes the stories of other eras emotionally immediate and moving, as if those eras were our own.

Machines of Another Era is available from Gold Wake Press.