When Heartbreak is Legacy

“I think only substance abusers fall asleep in the bathtub. / When I was little my dad used to warn me / to be careful in the bathtub because a few times / my mom almost drowned,” reads the opening poem of Sarah Bridgins’ debut poetry collection Death and Exes. It prompts the reader to wonder why a collection ostensibly about “exes” opens with a poem about parental death, addiction, and a portrait of unorthodox domesticity. While the poem does mention a boyfriend towards the end, it subverts expectations of what a typical journey of heartbreak, salvation, and healing may look like. In this way, the collection immediately challenges readers to reconsider what informs our perceptions of relationships. To Bridgins, heartbreak is informed by trauma that is intergenerational, cyclical, and inescapable.

Of course, there are plenty of ex-boyfriends and lovers throughout the collection. Bridgins transfigures them into dating-app archetypes — healer, the broken man-child, the needy one, the sensual one-night stand. There are the ones who are just as depressed as the author, and the ones who don’t understand the grief she feels on an atomic level. There are ones who stayed for a while, and ones the author pushed away. It seems less important for Bridgins to capture the full humanity of each ex than to excavate their core from herself, almost as if an exorcism. “It is a power, to repel men / this thoroughly, to be so damaged / it’s scary,” says a line from “Sea of Islands,” which reveals that perhaps the person who feels most dead to the author is herself. It becomes clear that this collection means to undo the notion that love can heal all wounds.

Throughout the collection, Bridgins is unafraid to make herself the unlikeable narrator. From another perspective, perhaps Bridgins would be described by an ex-boyfriend as the “crazy ex-girlfriend,” but who is the “crazy ex-girlfriend”? Are they some strange breed of undateable, unloveable women, who come from nowhere and infiltrate countless mens’ lives as they try to find wife material? Bridgins’ knows who these undateable and unloveable women are: women just like her, who are undateable and unloveable because they don’t love themselves. Bridgins does the tough emotional work of going through the rolodex of past versions of herself. They live together inside her like nesting dolls, and each poem hatches them back into our consciousness. There is the version of herself who lost her mother. The one who lost her father. The one whose mother was alive, but crippled by grief for a newborn who passed away. The one who has a job. The one who buys useless trinkets to find beauty in her life. The one who wants to die. “I have a strategy for times like these: / Keep your head to the ground. / Find a face-up penny. / Canadian ones count too.” It’s as if Bridgins wants to soothe not just herself, but every past version of herself through these poems. Each version of her had been broken in their own way, and bringing them together makes the author more whole.

In this collection, Bridgins is clear that unrelenting heartbreak makes a person feel outside of their lives, as if peeping in through a foggy glass, unable to interact fully. But there are moments of respite, which Bridgins explores through the non-romantic love in her life. First, love for self, which the collection rawly shows a deep internal struggle to feel. It seems easier to deflect this fear onto others by pushing them away, without acknowledging that pushing oneself away is just as painful. “I am simply collecting / more people to miss,” laments the author in “Red Shift” about fear of the dating scene, a poem that immediately precedes “Full Disclosure,” a poem about the fear of being alone. These poems juxtapose each other, unveiling a catch-22 that traps the author — unattainable desire to be loved without propagating already unbearable grief. Bridgins then turns toward healing this wound, since she is acutely aware that a broken self is not able to date in healthy ways. Here, another type of love comes in: the non-romantic love between friends. Part of what makes this collection so well-rounded and holistic is Bridgins’ keen acceptance of the flotation devices she has been given throughout life. Sometimes the things that save us are not dramatic, but can be as simple as a lifelong best friend.

The heartbeat of this collection is Bridgins’ ability to weave in how grief is inherited in her family. Before Bridgins ever had an ex-boyfriend or a lover or a crush, her heart was breaking because of the grief she was born into. “I come from a long line of women / who luxuriate in pain, / adorn themselves in velvet trauma,” Bridgins writes in “Summer Water.” When pain seems part of our DNA, what keeps us going? If our original heartbreak is an accident of birth, what is the roadmap forward?

Despite the central theme of grief, Bridgins’ collection is humorous, using macabre wit to explore suffering as part of the conditions of being a modern human, a depressed human, and a human who sometimes feels at odds with their humanity. “I do not own a microwave, / and using the oven makes me feel like I am cooking” and “This year, I planned to get you / the Dune board game, / and the ability to keep your blood / in your body.” Lines like these are conjured throughout the collection, most often at moments of emotional crescendo. When the pain of love is overwhelming, and strategies to self-soothe are ripping at the seams, Bridgins is able to place the reader almost startlingly back into their body. To inhabit a body involves quotidian and mundane actions to sustain life, which seem absurd in juxtaposition with the drama and heartbreak of our inner lives. Similar to how a toddler throwing a drawn-out tantrum will not pause just because its mother needs to pee, the body does not care what the heart needs. Bridgins shows through her work that the job of the heart is to keep pumping despite its suffering, because the body is relentless with its survival needs. It is precisely the bare bones requirements of keeping a body alive that can sometimes quell the sharpest heartbreak. In inhabiting a body, we learn to inhabit ourselves, despite death and trauma and grief, even despite our terrible exes.

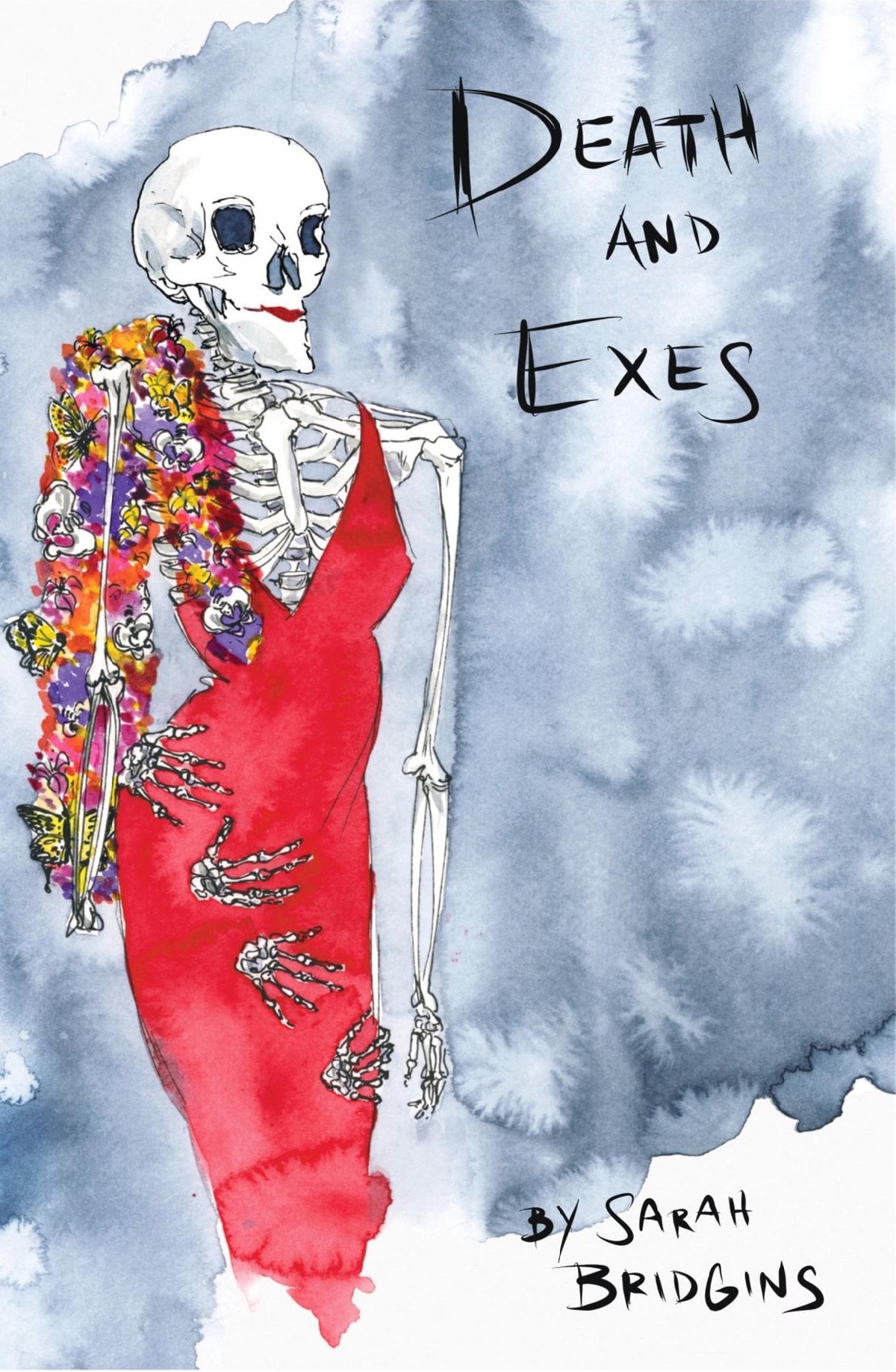

Sarah Bridgins’ debut poetry collection Death and Exes is available now from The Black Spring Press Group.