Dissecting the Dangers of Intersubjectivity

In Dario Argento’s 1975 giallo masterwork, Deep Red, the mystery is solved with an epiphany: the protagonist realizes that he had not seen a portrait at the crime scene, but the killer’s reflection in a mirror. The culprit was his best friend’s mother, not, as he suspected, the vengeful ghosts of an orphanage. A twist which demonstrates well a loathsome reality: how very close horror can be. I mention the film by way of synchronicity, for Bennet Sims, in his forthcoming story collection Other Minds and Other Stories, writes of the giallo director and Etruscan ceramicist who are each “scraping away at the same images, the one on jugs and the other on celluloid, both revealing the deep redness behind things.” Elsewhere, Sims colors the platonic base coat as the pale neutral canvas. The desire to uncover the hidden truth drives the collection’s narratives and characters. Argento’s mirror is a useful interpretive tool for Other Minds, as the subjectivities therein have the compromised veracity of a mirror-image; superficially accurate, but in fact reversed. Take for instance the self-regard of Kyle and Audrey in “Pecking Order.” Two self-professed “locavores,” who undertake the execution of their chickens thinking it more humane. As Kyle struggles in the night to behead his chickens with a blunt pair of garden shears, he confronts the bloody cost of his own naivete. They saw themselves as enlightened and countercultural but instead revealed themselves as misguided and superficial.

Dread is the collection’s defining mood. In the interview which ends the book, Sims cites “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” by Thomas Nagel — a major influence in his work. In the seminal essay, Nagel writes that for something to be conscious, there must be something that it is like to be that thing. Sims says that he “enjoys tracking the movements of [character’s] minds … deep into the territory of some other what-it-is-likeness.” But he doesn’t stop there. He pursues “character’s curiosity about each other until the sentences begin to spiral out into darker directions: paranoia, obsession, dread.” Sims’ characters defeat themselves as they rabidly pursue these benighted paths. In “Unknown,” the protagonist succumbs to a self-fulfilling prophecy, becoming what he feared his girlfriend might think he was — a smothering presence — because of his efforts to be sure, his refusal to let her think her thoughts. Sims’ characters have obviously not read Nagel, who famously (and controversially), concluded that the subjectivity of others is unknowable, and therefore lies forever beyond the reach of both semiotics and empiricism, or, in other words, cannot be ultimately described or observed. Nagel writes:

My realism about the subjective domain in all its forms implies a belief in the existence of fact beyond the reach of human concepts. Certainly it is possible for a human being to believe that there are facts which humans never will possess the requisite concepts to represent or comprehend.

Other Minds is a catalog of souls who lack the “requisite concepts,” and more dangerously, the existential nerve to live with unknowing. In “The Postcard,” the protagonist, a private eye, is swallowed by the crease between the past and present. Hired to investigate a postcard sent to their client from a character referred to only by their motel room number, “315,” the protagonist, also nameless and genderless, gets lost in their conjectures about “315”; the narration consists of varied lines like these: “315 could have been spooked by the sight of my car. They would have been expecting my client to arrive, they would be on the lookout for unfamiliar vehicles.” Those woulds and coulds imprison the private eye in a padded cell somewhere beyond the veil. While the investigative premise of “The Postcard” provides pretense for anticipating the thoughts of another, all of Sims’ characters are trapped in a chess game of their own making; trying to remain one step ahead of an invisible opponent.

Numerous stories in the collection present the high stakes of intersubjectivity, perhaps none better than “Unknown.” Two doctors, Decety and Moriguchi, argue that true empathy requires “a decoupling mechanism between first-person information and second-person information.” The man in “Unknown” — who quite literally is trying to prevent “decoupling” — does not assume the challenge of genuine empathy. Cannot accept that though there is “something that it is like to be a bat,” he can never gain full knowledge of his girlfriend’s inner life. Sims, through literature, has drawn the precise line between empathy and projection, paranoia and awareness. Something, which if we take Nagel by his word, is outside the purview of pathology. Thus, in Other Minds, Sims provides evidence for his own optimism about literature’s future; his belief that “as long as people are thinking interesting thoughts … writers will keep writing them down and readers will keep reading them. Even in the United States.”

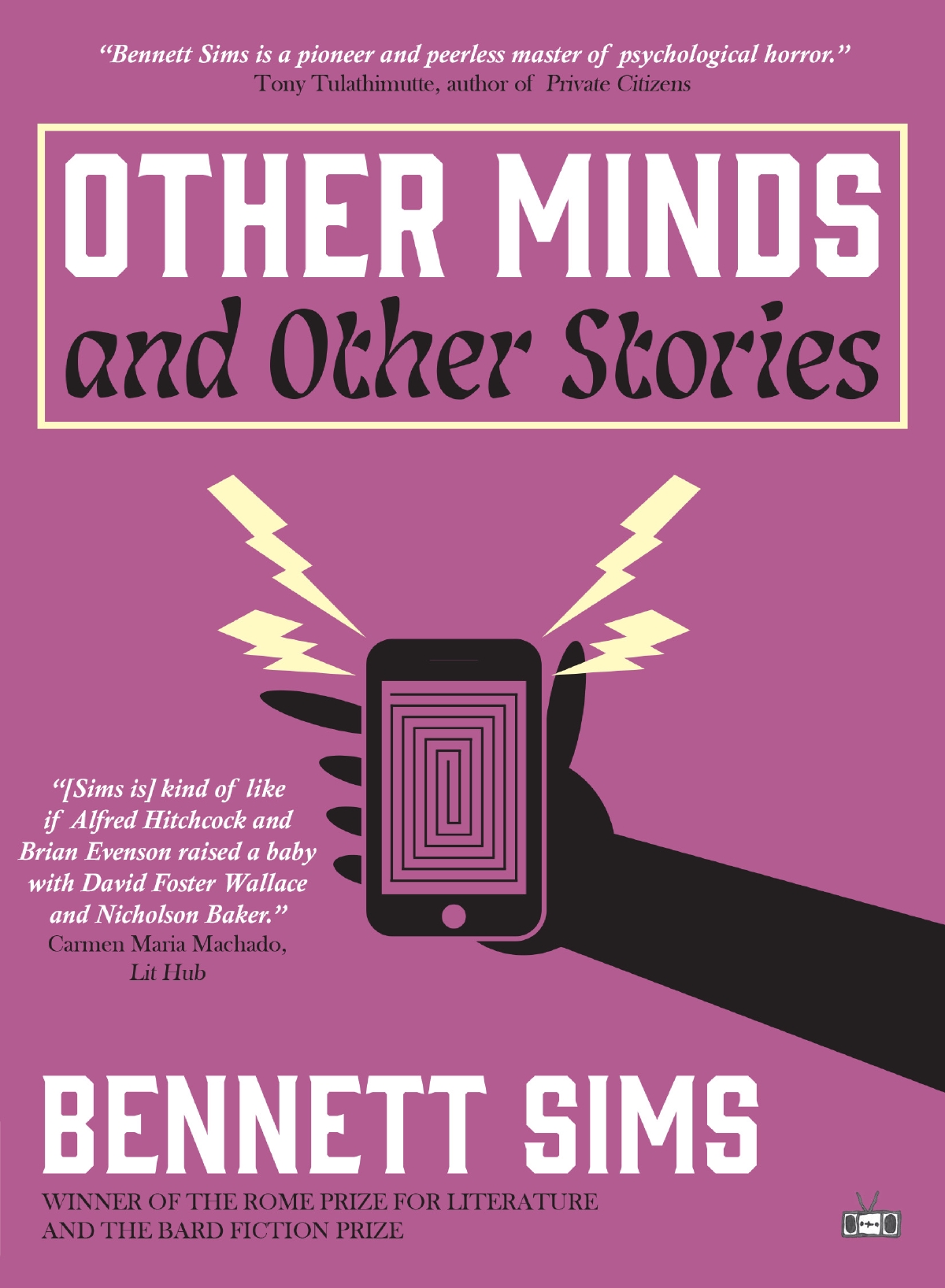

Other Minds and Other Stories is available now from Two Dollar Radio.